No. 12: “King of Hearts: The True Story of the Maverick Who Pioneered Open Heart Surgery”

Context at the end of this excerpt.

Other entries in #33Stories at the Table of Contents. See you tomorrow!

Originally published in 2000 by Random House.

Prologue: Red Alert. pp. 3 to 7 of "King of Hearts":

ON THE DAY that some feared he crossed over into madness, the surgeon C. Walton Lillehei woke at his usual hour, six o'clock. He ate his ordinary light breakfast, read the morning paper, kissed his wife and three young children good-bye, then drove his flashy Buick convertible to University Hospital in Minneapolis. The first patients of the day were already unconscious when Lillehei dressed in scrubs and entered the main operating area.

It was March 26, 1954.

Lillehei walked into Room II, where the doctors who would assist him were preparing two operating tables for the baby and the adult who would soon be there. Nearly all of the doc¬tors were young—younger even than Lillehei, who was only thirty-five. Most were residents—surgeons still in training who were devoted to Lillehei not only because he was an outstanding surgeon, but also because he seemed to live for risk and he overflowed with unconventional new ideas.

Lillehei checked on the pump and the web of plastic tubes that would connect the adult to the baby. He confirmed that two teams of anesthesiologists were ready, that the OR supervisor had briefed the many nurses, and that the blood bank was steeled for possible massive transfusions.

He confirmed that the adult—who was the baby's father—had not changed his mind about their being the subjects of this experiment, which no doctor had attempted before.

It looks good, said Lillehei. I think we're ready to go.

Elsewhere in University Hospital, a nurse roused the baby.

Thirteen-month-old Gregory Glidden was an adorable boy with big ears and a fetching smile that had endeared him to the staff during the three straight months they had cared for him. He was unusually scrawny, but at the moment there was no other outward sign that he was sick. His appearance was deceiving. Gregory had been born with a hole between the lower chambers of his heart—a type of defect that no surgeon had ever been able to fix. In fact, Gregory was dying. Dr. Lillehei doubted he would last the year.

Unlike many nights in his short life, Gregory had slept well and he awoke in good spirits. The nurse cleaned his chest with an antibacterial solution and dressed him in a fresh gown, but she could not give him breakfast; for surgery, his body had to be pure. A resident administered penicillin and a preoperative sedative, and the baby became drowsy again. Then an orderly appeared and spoke softly to Gregory about the little trip he would be taking—that he would travel safe in his crib, with his favorite toys and stuffed animals.

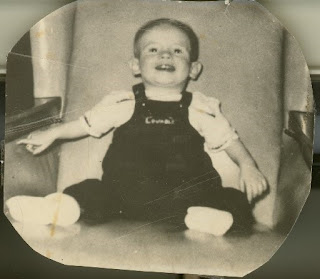

|

| Baby Gregory Glidden |

The Gliddens could never forget finding her body, cold and rigid in her bed.

It was half past seven. In the operating room next to Lillehei, Chief of Surgery Owen W. Wangensteen was cutting into a woman he hoped to cure of cancer. Wangensteen had not checked on Lillehei, nor had he told the young surgeon yet of the ruckus that had developed yesterday afternoon, when another of Universitys Hospital’s powers —Chief of Medicine Cecil J. Watson, an internist often at odds with Wangensteen —had discovered what Lillehei intended to do.

Watson already knew that Lillehei had joined the quest to correct extreme defects inside the opend heart —a race that so far had produced only corpses, in Minneapolis and elsewhere. He knew of Lillehei’s dog research —of hos the surgeon and his young disciples regularly worked past midnight in their makeshift laboratory in the attic of a university building. He’d heard of Lillehei’s new open heart technique, in which the circulatory systems of two dogs were connected with a pump and tubes; thus joined, the donor dog supported the life of the patient dog, enabling Lillehei to close off the vessels to the patient dog’s heart, open the heart, and repair a life-threatening defect. But until yesterday afternoon, when today’s operating schedule had been distributed, Watson had not known that Lillehei —with Wangensteen‘s blessing —was taking cross-circulation into the operating room.

This was madness!

Watson went to University Hospital's director, who alone had authority to stop an operation. The director summoned Wangensteen, and the three men had it out.

How could such an experiment be allowed? Watson demanded to know. For the first time in history, one operation had the potential to kill two people. Yet, paradoxically, how could the Gliddens refuse? They lived in the north woods of Minnesota, where Lyman worked the mines and Frances stayed home with their many children. They lacked the guidance of a human-experimentation committee, for none existed in 1954. They would never consult a lawyer, for they were willing to try almost anything to spare their baby their daughter's fate.

And was it any wonder that Wangensteen had blessed Lillehei? Of all the resplendent surgeons on Wangensteen's staff, Lillehei was unquestionably the crown prince—the most likely to bring the University of Minnesota a Nobel prize, which the chief of surgery all but craved. Blue-eyed and blond—a man who liked all-night jazz clubs and pretty women—brilliant Walt could do no wrong in Owen's eyes.

The chief of medicine was appalled. Had they forgotten the girl who had preceded Gregory Glidden in University Hospi¬tal's Room II, poor Patty Anderson, who'd been lost in a river of blood?

Gregory was brought into Room II and transferred to one of its two operating tables. His crib with his toys and stuffed animals was sent back into the hall and he was in the company of masked strangers. A doctor placed an endotracheal tube down his throat and turned the gas on.

Asleep, Gregory was stripped of his gown and left naked under the glare of hot lights. How small he was—smaller than a pillow, smaller than most laboratory dogs. His heart would be a trifle, his vessels thin as twine.

All set? Lillehei said.

The people with him were.

Lillehei washed Gregory's chest with surgical soap. With a scalpel, he cut left to right on a line just below the nipples.

Observers in Room II's balcony leaned forward for a better look. On the operating room floor, a crowd of interns and residents climbed up on stools.

Lillehei split the sternum, the bone that joins the ribs, and opened a window into Gregory with a retractor.

Nestled between his lungs, Gregory's plum-colored little heart came into view. It was noisy; with his hand, Lillehei felt an abnormal vibration.

Still, the outside anatomy appeared normal: the great vessels were in their proper places, with no unnatural connections between. So far, no surprises.

It looks okay, Lillehei said. You may bring in the father now.

-- 30 –

READ the paperback

READ on Kindle

LISTEN to the audiobook

Context:

The fourth book (after “Toy Wars”) published by Jon Karp at Random House before he left to head another house, Twelve, “King of Hearts” has its roots in the first Jon bought, “The Work of Human Hands.” The protagonist of tha, Dr. Hardy Hendren, invited me to a lecture by a surgeon I had never heard of, Walt Lillehei, at Children’s Hospital a few years after it was published. I went.

Almost from the moment Walt began speaking, I was mesmerized. And when he began showing slides of his work in the Wild West that was heart surgery in 1950s, I was hooked. Over dinner at the Harvard Club that evening – Hardy had deliberately seated me next to Walt – I asked Walt if anyone had every written a book about him and his pioneering work.

Well, no, not really, Walt said. Been mentioned in a few books, but that was about it.

Would he agree to let me write one?

Well, sure, Walt said. He really was that easy-going.

|

| Walt Lillehei with an early patient |

Eventually, I made it to Minnesota – several times – where Walt opened his life, his records, his patents, everything, to me. It was pure gold.

Walt was sick by the time I finished the first draft of “King of Hearts” and he would die just a few months later. But I sent him that draft for his check on accuracy, and he indeed read it. He found a few incorrect minor details but otherwise blessed the book and said it had wonderfully captured him, his work, the work of others and that era. He did insist, however, on what he considered a more important correction:

I had the wrong name of the bar he frequented near New York Hospital-Cornell Medical Center in Manhattan where he later was Chief of Surgery.

It was The Recovery Room, Walt said.

I made the correction.

And that, too, tells a lot about the wonderful and wonderfully complex person who was Walt, whose work directly – and indirectly through the many surgeons he trained, and later generations trained by them – saved more lives than one could ever calculate.

King of Hearts was a critical and commercial success, and I always thought it work nicely on screen, as either a feature-length movie or TV series.

We had some nibbles over the years, and my screenwriting partner Drew Smith and I wrote scripts and treatments, but to date, all talk, no action. I still have great hopes, since surely one day someone in a position to make it happen will agree that there has never been quite a real-life drama like the narrative, nor a character like the protagonist, the man who became a dear friend, Walt Lillehei. RIP Walt. No one like you ever.

BUT as I often am reminded, fate is a funny thing. About a year ago, I was contacted by a young journalist from China, Caroline Chan, who was working with a documentary crew from CCTV, China Central TV, the main state television broadcaster in China. The crew was working on a series about the history of medicine for what can be called CCTV’s Discovery Channel – would I like to participate, bringing the story of “King of Hearts” to the screen?

Yes! And so, long story short, I travelled to Minnesota for four days last summer and we shot at multiple locations, including the home of Mick Shaw, one of Walt’s early survivors. It was an amazing moment for all of us.

You can learn about that and more on the King of Hearts Facebook page.

Watch for the episode later this year or next – no date yet – on CCTV. Here is the English-language CCTV site: http://tv.cctv.com/cctvnews/

And while I have lost touch with most of the other still-living people from King of Hearts, I would like to mention, as I did in the book, that the Glidden family, given their economic circumstances, had never been able to afford a proper tombstone for young Gregory. They accepted my offer to help pay for it, and I penned his epitaph: "His little heart changed the world."

Some of the reviews for King of Hearts:

"Exhaustively researched, novel-like... Few people outside of medicine have heard of Lillehei, and few remember the sweaty-palmed suspense of open heart surgery's early years. It is fortunate that Lillehei has posthumously found Miller to rectify his anonymity. The resulting tale grips like a surgical clamp and doesn't let go."

-- Forbes magazine, January 24, 2000

"The Invention of open-heart surgery is an epic tale of caution and recklessness, genius and serendipity, selflessness and megalomania. Until now, it was a story available only to readers of scholarly books and journals. With King of Hearts, G. Wayne Miller has given this great story to the rest of us... And he has written King of Hearts with clarity, simplicity and grace."

-- Associated Press, February 14, 2000

"The wrenching stories of these children, the sacrifices of their parents, and researchers' incredible experimental efforts to divert blood from damaged hearts using dog hearts or the living bodies of donors make for riveting reading... Highly recommended for all readers."

-- Library Journal, January, 2000

"G. Wayne Miller has written one of those books that makes you wonder why no one had done it before. The remarkable story of flamboyant heart surgeon Walt Lillehei's pioneering work in open-heart surgery clearly ranks with the most important of modern times, and Miller has told it in a breathless, spirited, and dramatic way in King of Hearts... It is science writing at its best."

-- Mark Bowden, Philadelphia Inquirer, May 7, 2000

"King of Hearts is The Right Stuff of open heart surgery."

-- Jonathan Harr, author of the bestselling A Civil Action

"Wayne Miller's book is a roller-coaster account of this extraordinary man's life and achievements. By moving back and forth in time, he builds suspense and keeps the reader turning pages to see what miracle will next come from Lillehei's hands. It reads like the best of suspense novels."

--Decatur Daily,, December 31, 2000

"The book is ultimately a story of triumph against all odds."

-- Asian Cardiovascular & Thoracic Annals, Vol. 9, No. 1, 2001

"With gripping detail, Miller's book takes the reader inside the hospital's walls back in the 1950s and 1960s. He shows us anxious parents waiting to see if their desperately ill children would be the lucky ones that Lillehei could save. His heart surgeries were high-wire acts performed without a net. And with the instincts of a good showman, his academic lectures included photos of his grateful patients, not shot in hospital gowns, but dressed in cowboy and cowgirl outfits."

-- Los Angeles Times, March 6, 2000

"There are a lot of good stories to tell from the `country of hearts' (as the cardiologist and poet John Stone has called it). But these are more than simply good stories. Important ethical, emotional and financial dilemmas -- sometimes all three--are posed by the narratives of innovation in heart medicine."

-- Washington Post, Sept. 3, 2000

"The beauty of these fascinating tales lies in the detail and the personal interactions of the players. By means of interviews, datacollection, and other extensive research, the author conveys the essence of the early days of open-heart surgery...King of Hearts extensively chronicles the life of its main character and weaves together significant contributions of many other pioneers ofcardiac surgery. The author's end notes are a bonus. They contain a wealth of detail on events, equipment, and people involved in theformative days of open heart surgery."

--Journal of the American Medical Association, June 21, 2000

"This book by G. Wayne Miller is a thorough and entertaining biography of Walt Lillehei presented fromhis own perspective as well as that of his patients and his contemporaries. The reader gets a real sense of theadventure, the urgency, the excitement, and the disappointments of laboratory and clinical research during the exciting first two decades of cardiac surgery...Those who knew Walt Lillehei will agree that his scientific fervor and accomplishments, his brilliant laboratory studies and bold clinical innovations, his flamboyant style,his sometimes troubled but always colorful personal life, and his work-hard, play-hard character are all accurately represented."

--New England Journal of Medicine, June 29, 2000

"Highly recommended for all audiences."

-- Choice Magazine, July 2000

"No ordinary biography, King of Hearts is breathless reading--you'll find yourself surfacing every few chapters to remind yourself it's nonfiction."

-- amazon.com, February 4, 2000

"Dr. Walt Lillehei was one of the unsung heroes of surgery in the 20thcentury. King of Hearts is a fascinating and suspenseful inside portraitof how this pioneer blazed a trail for all heart surgeons. It is a storyof historical importance, and Wayne Miller tells it with precision andgreat spirit."

-- Dr. Christiaan Barnard, heart transplant pioneer

"Fascinating medical history... Miller tells Lillehei's story with elegance and an immediacy that keeps the medically complex story from getting boring...This medical pioneer was far from a moral paragon, but Miller never allows his subject's deficiencies to detract from the glory of his medical accomplishments. In fact, the contrast between Lillehei's personal and professional lives spices up King of Hearts considerably."

-- The Fort Worth Star-Telegram, June 18, 2000

"The book may be read on several levels -- as a medical thriller, a historical record, or a fascinating personality study.Indeed, in its grand themes of life and death, power and temptation, it is reminiscent of a Greek tragedy, whose herorepresents humanity itself.''

-- Texas Heart Institute Journal,, Vol. 27, No. 2, summer, 2000

"Chief among its pioneers was the intense and flamboyant Minnesota surgeon Dr. C. Walton Lillehei, whose story Miller tells here in thriller style. Miller, a staff writer for The Providence Journal, re-creates the anxietiesand excitement of an era poised on the brink of astonishing technologicaladvances... Miller's fast-paced and scrupulously researched account revealsboth the exhiliration and the tragedy of Lillehei's story."

-- Publishers' Weekly, December 20, 1999

"Miller skillfully describes the years of research that finally led Lillehei to his first cross-circulationoperation on a human... a sturdy telling.''

-- The Boston Globe, May 12, 2000

"An unflinching, blood-and-guts look at the science and despair of modernopen-heart surgery, framed by a biography of a giant in the field, Dr. C.Walton Lillehei... With the medical profession under financial siege,Miller's breathless, suspenseful reminder of thelife-and-death-but-mostly-death drama of medical research, as well as thepathological risk-takers that drive it forward, could not have come at a moreopportune time."

-- Kirkus Reviews, January 1, 2000

"Miller calls himself 'one lucky writer,' and anyone who picks up his informative and enjoyable biography of pioneering heart surgeon C. Walton Lillehei can become one lucky reader."

-- Booklist, January 2000

"The book reads more like a perfectly written thriller than it does a nonfiction book -- one page into the story and you'll be absolutely riveted by the unfolding drama."

-- Writers Write recommended book, February 2000

"The book may be read on several levels—as a medical thriller, a historical record, or a fascinating personality study. Indeed, in its grand themes of life and death, power and temptation, it is reminiscent of a Greek tragedy whose hero represents humanity itself, vulnerable to flaws and errors in judgment. Aimed at a lay audience rather than at medical professionals, King of Hearts will be enjoyed by all who relish a gripping narrative."

-- Dr. Denton A. Cooley, legendary Texas surgeon, writing for Texas Heart Institute Journal, 2000; 27(2): 224–225

"Miller casts his "King of Hearts" as a romantic tale of a flawed and passionate genius."

-- Minneapolis Star-Tribune, March 5, 2000

"What Miller has done is recapture the high drama of the race to work inside the human heart."

-- Providence Sunday Journal, January 30, 2000

"(An) engaging work of modern medical history."

-- Winnipeg Free Press, April 16, 2000

"An epic writ in blood."

-- East Brunswick (N.J.) Home News Tribune, February 20, 2000

"Highly recommended reading for parents, adult patients, and medical professionals!"

-- Mona Barmash, Children's Health Information Network, February 21, 2000

"This compelling book by Wayne Miller has beautifully captured the intense drama of the fifties and sixtieswhen everything was happening... not to be missed by anyone involved in heart surgery and by all who aspireto be complete heart surgeons."

-- Indian Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, June 2000

"Written in the form of a fast-paced, dramatic thriller, this book is sure to rivet your attention... In this elaborately researched work, (Miller) has captured the magical moments that were those early days of heart surgery."

-- Heart Beat Healthzine, January 2000

Recommended non-fiction title.

-- Barnes&Noble.com, week of March 6, 2000

Such an amazing article indeed. You can also look for a heart transplant. Many countries are now available to this service and the transplants are offering them a new life with better sites. They no longer need any extra surgeries like a bypass.

ReplyDeleteThat “two tables, one heartbeat” scene floored me—equal parts reckless and visionary. The Recovery Room detail humanizes Lillehei. Curious: how would modern consent boards view cross-circulation today? For everyday prep, this clarified can you eat before a cardiology appointment.

ReplyDelete