READ AFTER THIS INTRO: One of my favorite interviews ever... of my still-favorite author.

If you will pardon the pun, look between the lines (this one, for example:

Suddenly, without warning, the lines on King's face deepen, his eyes become cat slits and he's baring his teeth...) and you will see evidence of King's then-cocaine addiction, unknown to the world at the time but later very public when King himself wrote and spoke about his struggle. He's been clean and sober for decades now.

BUT

then -- during this interview -- he was deep into it. Every few minutes during my hour-or-so-with him he jumped up, disappeared into a back room of his hotel suite, and returned,

even more animated and hyper than before. Little did I know. I just thought he was, well, full of energy.

Another note: King was in a suite on an upper floor of a hotel overlooking New York City's Central Park (I forget which one, maybe The Pierre?). I waited in the lobby for a publicist to take me up and when the elevator opened, who stepped off but the now-disgraced Today Show ex-host Matt Lauer, who had just interviewed King for Fox affiliate WNYW, the NYC station he'd joined after leaving PM Magazine, Channel 10, Providence. We said hello; I knew him peripherally. No clue, of course, what awaited him...

And one more note, if I may?

King's editor then was the late Alan Williams, one of publishing's greats. He happened to be the editor who bought and published my first book,

Thunder Rise. How glorious that was, and how long ago. I can recall like yesterday sitting in his mid-town Manhattan office discussing the book, which my first agent, the wonderful Kay McCauley, sister of then-King agent Kirby McCauley, had sold.

OK now:

The Providence Journal

KING OF HORROR: His career's in 'Overdrive' as he directs his first film

Publication date: 8/3/1986 Page: I-01 Section: ARTS

Byline: G. WAYNE MILLER

STEPHEN KING, the most popular horror writer of all time, is eating pizza - thick, oily, mega-calorie pizza with all the fixings. He's eating it the way a big hungry kid would - ferociously and noisily. Stephen King loves pizza, just as he loves scaring the pants off people.

King, who has made enough money from what he calls his "marketable obsession" to buy Brooks Brothers' entire inventory, is dressed in jeans, work shirt, running shoes. Comfort is the thing for King, who sets many of his stories in rural Maine, the place he's lived most of his 38 years.

Would his visitor like a slice of that greasy monster masquerading as a pizza, he asks politely? No? Then have a seat. Feel at home.

He sits - flops is probably a better word - onto an oversized chair in his hotel suite. King is well over six feet tall, and his long legs seem to stretch halfway across this elegantly furnished sitting room. He brushes his black hair off his face, grins mischievously, and peers from behind thick glasses, his "Coke bottles," as he's referred to them.

"Whatever you want to talk about," he says in a voice that is a curious mix of Downeast twang and Ted Kennedy drone. "The film is what I'm supposed to talk about, so why don't we start with the film?"

Maximum Overdrive, King's first shot at directing, opened last weekend. It's about a group of people trapped by driverless vehicles in an isolated truck stop the week all the machines in the world go murderously beserk. Machines gone mad. It's a favorite King theme, and if one were to psychoanalyze it, the connection to modern man's uneasy coexistence with his nuclear genie would be hard to miss.

The obvious first question, of course, is why a one-time teacher who has parlayed a lifelong fascination with the macabre into a fairy-tale existence as best-selling author (70 million books in print) would want to trade his golden pen for a camera.

Certainly, King is no stranger to movies. He admits to being a horror-movie junkie growing up in the '50s and '60s; as an adult, he has written the screenplays for five films, including Overdrive. Eight of his full-length novels have been made into films of varying quality, and another four (including Pet Sematary, his most recent) are in various stages of production. On top of all that, several King short stories have been adapted for TV, and an unpublished novel has been sold for a mini-series.

So why direct?

"Curiosity," he says, continuing to gorge himself on pizza.

Actually, it wasn't simply curiosity that prompted King to accept movie mogul Dino De Laurentis's offer to direct.

Pleased with some

Although King is pleased with some film adaptations of his works - he thinks Cujo and The Dead Zone are great - he has been disappointed with others. In particular, Firestarter, Children of the Corn, and The Shining, directed by Stanley Kubrick, still make King cringe. (He once described Firestarter as "flavorless," like "cafeteria mashed potatoes.")

The disappointing films, King explains between bites, failed to capture the spirit of his written works - either they didn't frighten, or took implausible twists, or were blandly acted, or sloppily directed, whatever. With Overdrive, King finally wanted to see if he could capture that spirit on film. If he couldn't, well, at least he'd have no one but himself to blame.

"My son's got this wonderful imitation of Leonard Malton on Entertainment Tonight," King says, becoming suddenly animated.

"He'll start off the way he always starts off when he's going to give a really bad review. He'll say, 'This is Leonard Malton, Entertainment Tonight. Stephen King says that he wanted to direct a picture to see if whatever makes his books so successful could be translated to film if he did it himself.

" 'The answer is no]' "

King grins. "Actually," he continues, "the answer is yes. I think. I think it has a lot of appeal of the books."

Not that he's exactly rehearsing his Academy Award acceptance speech, as he notes wryly. Although the film does not look amateurish - for a rookie, King's grasp of cinematic technique is quite impressive - its human characters are undeveloped. And despite King's hopes, Overdrive only hints at his books' rich textures. It's hard to escape the conclusion that what King does so well in print probably can't be translated onto the silver screen.

"I think by and large this movie will get kind of a sour critical reception," he predicts. "It's a 'moron movie,' for one thing. It's crash and bash. It's a head-banger movie - really, really loud."

Promotional tour

Critics notwithstanding, King believes audiences will like Overdrive as much as he does. He hopes so, anyway. The only reason he agreed to do a nationwide promotional tour is to hype the film. Too many earlier King films, he laments, have lasted in theaters all of two weeks.

"Graham Greene said . . . writers write books they can't find on library shelves. To some extent, I think directors must direct movies that they can't go and watch in movie theaters.

"Overdrive is fun. I like movies where you can just, like, check your brains at the box office and pick 'em up two hours later. Sit and kind of let it flow over you and, you know, dig on it. This movie is just sort of gaudy blaaaaah. It's not a heavy social statement," he asserts.

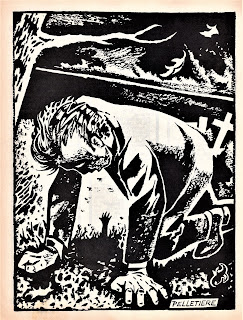

Suddenly, without warning, the lines on King's face deepen, his eyes become cat slits and he's baring his teeth - he's got one hell of a set of incisors, one discovers. Normally a rational and intelligent human being, he's transformed himself into a raving lunatic.

He jumps up and screams: "One of the things I wanted was to never let up. My idea is that what you do is build up, like reaching out and grabbing somebody by the ----] Right out of the page if possible or right out of the screen] Tell you what, ------------, you're mine]]]]]]"

He sits down again, laughing like - like a kid.

Four new novels

To say that Stephen King is big is a little like saying Carrie, telekinetic murderess of his first novel, is odd.

Some noteworthy footnotes to the King saga:

* The initial hardcover printing of last year's Skeleton Crew, his second anthology, was one million copies, one of the largest first hardcover printings in publishing history.

* King books are hot collectors items. In May, for example, an uncorrected proof of his Night Shift collection brought $2,500 at a San Francisco auction. A small-press magazine in which one of his stories appeared years ago brought a cool $150.

* For a decade, King's books have consistently topped the best-seller lists. According to Publishers Weekly, his scorecard for 1985 included the fifth and 11th best-selling fiction hardcover books; the second, fourth and eight best-selling mass paperbacks; and the second and third best-selling trade paperbacks. Total sales of those seven books alone: 11.49 million.

* King has his own monthly newspaper, Castle Rock, published and edited by his secretary, Stephanie Leonard.

* Against the advice of his publisher, who's worried that the market will be saturated (King disagrees), King will release four new novels in the next year, including the 1,000-page-plus IT later this summer.

* A musical version of Carrie takes to Broadway this fall.

Not to mention all those movies.

This being America, money has come hand-in-hand with his fame. King is so rich that when someone threatened to buy his favorite radio station in Bangor, Maine, and replace its rock format with EZ Listening, he rushed out and bought it himself. Rumor has it he paid cash.

The unknowns remain

Naturally, there are secrets to King's success.

One - hardly the best-kept - is that people, millions of them, anyway, like to be scared. Late at night, with the wind moaning, the leaves on the trees rustling, the kids sleeping (are they still breathing?) and something downstairs making a strange noise (is it only the cat?), they love to curl up with a good scary book and let the chills crawl down their spines.

King has lectured and written extensively about fear. He understands that no matter how technologically advanced we become, no matter how much the scientists figure out about ourselves and our world, the great unknowns remain: darkness, death, whatever is beyond the grave.

Still, there are plenty of horror writers slogging away out there, including several who have won critical acclaim - such as Robert Bloch, who wrote Psycho, and Peter Straub, author of the million-seller Ghost Story, and J.N. Williamson and Richard Matheson, two of the more prolific writers of the genre. Some are literary, closer to Poe than King; others are more gruesome, more skilled with plot. In terms of popularity, King has eclipsed them all.

The real secret is where King has taken horror - out of the Egyptian mummy's tomb and straight into the living rooms, bedrooms and kitchens of contemporary middle- and lower-class America. King's landscape is the America of kids and pets and Coke and malls and cheeseburgers and troubles with the mortgage payment and that old clunker, the family car - much the same vision of America that Steven Speilberg has brought to Hollywood.

Not that everything is ordinary in King's works. Whether haunted car or haunted child, King's villains and monsters and spirits are deeply troubling, frequently uncontrollable, and usually deadly. There's a lot of darkness in King's work, and plenty of ghosts. Death is never very far away.

It is precisely this juxtaposition - ordinary people victimized by extraordinary forces - that is the key to all good horror, not just King's.

Hitting the nerves

Still . . . 70 million books, 16 movies, a Broadway play, and no end in sight?

"Some of it," King explains as he polishes off lunch, "has got to be that I'm talking about things that, like you say, hit nerves. Or maybe they don't hit nerves - maybe they just resonate.

"You know, people say, 'I know about that, because that happened to me.' I don't mean an ability to light fires or anything like that (the heroine of Firestarter is a young girl with pyrotechnic powers), but something about family life, or something your kid said, something like that."

Not that King's intent is anthropological exposition; he is not a scholar, nor does he pretend to be. He bases his fiction on situations he understands because they've been his life, too - family, marriage, the battle (at least in the early days) for a buck. King and his wife, Tabitha, also an author, have three children. The eldest is 16.

"I don't write with an audience in mind. I mean, the audience is me. My popularity says something about my own mind. It's a little bit distressing when you think about it. It says, 'Well, here's a person who's so perfectly in tune with middle-cultural drone that there must be this incredible bowling alley echo inside his head.' "

Even King's detractors - there's no shortage of critics who dismiss his work as insignificant - concede that he has a true talent for depicting children. Maybe that's because King himself could well be the biggest kid in America. Even when they are blessed/cursed with supernatural powers, King's fictional children are flesh and blood - so seemingly real that you wonder if they don't actually exist somewhere, and King is only documenting their lives.

In fact, King's own children have had enormous impact, and if you doubt that, you only need look at his dedications.

"I grew up with them," he says. "Bringing up baby or child or children or whatever has been one of the experiences of my life, and so it's one of the things I write about. But also it's a way of trying to make sense of how the child you were yourself became the man that you are and that whole crazy business."

Woes with women

As good as King has been creating children, he has had his woes with women, as countless critics have been quick to point out.

"I've had such problems with women characters," he agrees, the smile leaving his face. "God knows I have tried. I tried with Donna Trenton in Cujo - tried to make a real woman. (I thought) she worked pretty well, except I got hit pretty hard by a lot of critics. An awful lot of critics said the dog is punishment for adultery.

"The death of her child . . . consciously, on top of my mind, I was simply trying to create a convincing chain of events that would put the boy and her in that position where they could spend a period of time. But when you think about it. . . .

"Yes, I've had trouble with women. It's funny because that's why I started to write Carrie. This friend of mine said to me, 'The trouble with you is you don't understand women.' I said, 'What do you mean?' It's like he'd accused me of being a virgin or something like that, which I just barely wasn't at that time.

"He says, 'Ah, all these stories with these hairy-chested horror things, these guys fighting monsters and stuff like that.' I was trying to tell him, 'You don't understand. That's what they buy, these men's magazines.' He said, 'You couldn't create a woman character if you tried. You know, a good one.' I said I bet I could. Carrie - that's a book about women, almost completely about women. There are almost no male characters in it."

Father ran off

By now, the story of King's climb to the top is legendary.

It begins with a kid growing up in Maine and (for four years) in Connecticut - a kid whose father ran off never to be heard from again, a kid whose mother raised him and his elder brother on a shoestring. On the outside, King was a polite child who liked cars, played some sports - but inside, he would later recall, he often felt unhappy, "different," even violent.

He remembers writing his first horror story at the age of seven; it was about dinosaurs on a rampage. Through his teens, he read voraciously, spent hours in movie theaters, kept on writing and writing and writing. It was while attending the University of Maine, Orono, that he began to sell short stories to magazines. But his novels, and there were several of them by this point, were going nowhere.

After college, he and his wife worked a succession of jobs to keep their family afloat: Tabitha as a waitress, he as a worker in a coin laundry and as an English teacher at a private school. The short stories kept selling - they were helping to pay the rent on the tiny trailer where they lived - but the novels were still moribund.

King wrote Carrie working late into the night in the furnace room of their trailer - the only available space in already cramped quarters. Somewhere, King says, they still have the Olivetti portable typewriter on which he banged out several early novels and stories.

The old portable

"There were no word processors then," King remembers. "I used my wife's portable. She stills says sometimes - in jest, I think - 'My husband married me for my portable typewriter.' It's got my fingerprints carved into the keys. I mean, I beat that thing to death just about.

"I used to have to bring Joe in in his crib to where I worked, which was the furnace room. You'd get hot and you'd be going along good and he'd wake up and you'd have to give him a bottle because he'd cried. It was just, you know, you get it done the best you can.

"You don't raise your head and look around, because if you do you just get depressed. And I was depressed then. Because I was selling some short stories, but I had had like three, four novels bounced back at me at that time and also a number of other short stories."

Even after finally selling Carrie to Doubleday, the struggle continued.

"My wife used to work at 'Drunken' Donuts,' which is what they called it on the night shift. I used to take care of the kids while I did the rewrite. This was after the contract and everything, but before we had any money. I mean, the contract was only for $2,500. It wasn't exactly a king's ransom," he says, seemingly unaware of the pun.

The big break came with the paperback contract for Carrie, which had done reasonably well in hardcover. King had expected to earn $5,000 to $12,000 on the paperback rights. When his editor called to tell him that the sale had been for $400,000, virtually unprecedented at the time for a newcomer, he was flabbergasted.

He celebrated by buying the thing he thought his wife would like the most - a $29 hair dryer.

'Normal' life in Maine

It seems a lifetime ago, those early days.

Today, King and his family live in a large Victorian house in Bangor. He has a summer home on a Maine lake, drives a Mercedes, is a Red Sox fan, loves beer as much as pizza, enjoys tennis and softball, usually wears a beard in winter. Except when he's on tour, he writes every day of the year, except Christmas, the Fourth of July and his birthday. He does the family shopping. His children attend public schools.

"They don't have any sense that there's anything really odd about what I do because I've never made out like I'm a big shot because I don't feel that I am. Also, we don't live in New York or California, where they might live in an atmosphere that's a little stranger. They seem pretty normal."

Although he is Bangor's most famous citizen - arguably Maine's, as well - the natives, he says, "mostly leave me alone. I have the town broken in. I guess familiarity breeds contempt."

Not that he hasn't become something of a celebrity for the tourists - a class of citizen he has often lampooned in his written works.

"Oh, sure," he says. "They have Canadian tour buses that come down to go to the mall - the Bangor Mall, which is the closest real big super mall to Nova Scotia. One of the things they throw in with this is you get to go by the 'Stephen King House,' like you're stuffed and embalmed. You're in there and one day you look out and you see this huge bus with 150 Canadians lined up along the fence snapping pictures. It's very odd."

Next interview

A TV crew has arrived early to set up for King's next interview. "Let's go into the bedroom," he suggests. "It's quieter." He gets up, crosses the room and closes the door behind him. Stretching full-length on his unmade bed, he props himself up on his elbows and resumes talking about his film.

Overdrive is based on "Trucks," one of several brilliant short stories in his first anthology, Night Shift.

"It's always been my favorite from that collection," he says. "Trucks I liked just for the feel of it. It had a desperate film noir quality as a story."

Machines gone mad. In Overdrive, which will be remembered more for its special effects and pyrotechnics than its acting or social significance, they go one step further: They try to take over the world. Knives, soda machines, video games, lawnmowers, a drawbridge, cars, 18-wheelers - all become killers.

"I'm fascinated by (machines)," King says enthusiastically. "They scare me. There's so much potential for destruction. In the film there's a track shot that starts on this hammock that's empty and swinging. In the background you see a guy who's obviously had his head cut off by his own chainsaw. The chainsaw is buried somewhere in his neck.

"There's a little Watchman with a little teeny screen giving this information about machines having gone beserk. The camera pans down and tracks and you see an overturned Styrofoam cooler and then you see empty beer bottles and then you see the Watchman. It doesn't have a picture on it but it's splattered with blood.

"Then you see the guy and you track up his body and he's all been shredded because he's been, you know, 'lawn-mowered' to death. You come to the lawnmower itself and it's all covered with blood and everything. When it finally runs, it chases this kid. It's quite funny."

He chuckles, then pauses. "Well to me, it's funny," he explains. "A lot of people are going to say it's gross and gratuitous. That's OK."

Machines and actors

King chose Overdrive for his directorial debut because he thought it would be easier to work with special effects and machines rather than with real-life actors.

It turned out to be the other way around.

"I thought to myself: 'My electric knife is never going to say, 'I can't cut the actress's arm today because my hairdresser didn't come in from New York.' My truck is never going to say, 'I can't run by myself today because I'm having my period.' You know what I mean?

"I went into the thing with a lot of the stereotyped ideas that people get about actors. You know, 'They're a bunch of conceited snobs. They're all babyish, you have to baby them along, you have to always be feeding them constant praise, they're always difficult to work with,' all this stuff.

"It turned out all to be b-------. They all worked really hard. They gave me more than 150 percent. They were almost always at their best.

"The actors were great, but all the machines . . . they wouldn't run. The trucks wouldn't start. We crashed four vehicles that were supposed to roll over before one finally did, and that was only on the third take. We had problems with the power mower. It was radio-controlled. Back at the studio, it went like a bat out of hell. Get it on location, it would just sit there.

"The electric knife that goes beserk . . . skittering along the floor like a big bug. The special-effects guys built three knives using dildo motors - basically vibrator motors to make them work. Two of them got wrecked on bad takes and we only had one left and we had to get it right. Luckily we did."

What scares him

The TV people are ready and time is almost up.

A few questions remain.

What scares you?

"Just about everything, in one way or another," he says. "But I think the thing that scares me most would be to check on one of my kids one night and find him dead in bed."

Did you ever expect to sell 70 million books?

"I don't even know what that figure means," he says, as if still finding it impossible to believe. "Do you realize if I live along enough there could be as many copies of my stuff actually sold as there are people in the country?"

No, King never expected all this - not even in his wildest dreams.

Are you afraid that someday it'll all be gone?

"Yeah," he laughs, starting to act out a scene from a movie where an enormously fat man explodes after a gargantuan meal. "Someday I'll just burst like that guy in Monty Python's The Meaning of Life. Did you see that? 'Just one more mint.' 'Nah, I'll burst'. . . and he did."