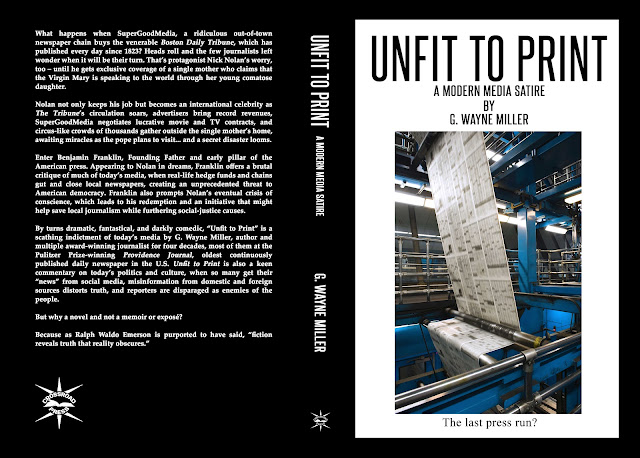

The Kindle, Nook & Apple Books editions of "Unfit to Print: A Modern Media Satire" were published on September 20, 2023, and the print edition was published on September 22 (earlier than the original publication date of October 10!). The audio edition will be published by October 10. Choose your seller:

Choose your seller:

-- Read select excerpts on Google Books.

CHAPTER ONE: Market value

Once upon a time, I, Nick Nolan, wrote exclusively

about marginalized people who had little or no voice in the mainstream media.

Socioeconomic and health disparities, mental health, and intellectual and

developmental disabilities were among my topics. My stories prompted change.

Some won awards and three were Pulitzer finalists — but, more importantly, I

helped advance the social-justice agenda as only a crusading journalist can do.

When I left hard news to become a columnist, a move I

believed would afford me greater power to prompt change — think Anna Quindlen

and Nicholas Kristof — I was merciless when I took aim at corrupt politicians

and judges, self-serving civic leaders, misogynists, unethical corporations,

climate deniers, opponents of LGBTQ+ rights, and racists and demagogues

wherever they were found.

My column was always on the front page, I was nationally

syndicated, and I hosted a popular TV show. My website, Facebook, Twitter,

Instagram, and YouTube accounts had hundreds of thousands of followings. Simon

& Schuster published a collection of my columns and in its review, The

New York Times proclaimed me “brilliant.” The Los Angeles Times went

further, calling me “a writer who eloquently frames truths. The world needs

more Nick Nolans.” Promising millions, a Netflix producer had reached out to me,

wanting a pitch for a series about the newspaper business.

How long ago this all seemed the morning we

learned that our newspaper, the family-owned Boston Daily Tribune, had

been sold.

It was August 23, 2021, the second year of the coronavirus

pandemic.

By then, my social media activity was tepid.

By then, my column was buried deep inside metro/region.

By then, not even bottom-feeder agents contacted me.

By then, the January 6 insurrectionists had stuck another

dagger into the heart of democracy — and out-of-town and hedge-fund newspaper

chains that paid their executives obscene salaries and bonuses while laying off

actual journalists as they ghosted and killed local papers were pushing it in

deeper.

By then, my muse had forsaken me.

More correctly, the muse had been slain.

Using Google

Analytics, a member of our marketing staff had “proved,” as he phrased it, that

social-justice columns did not generate the numbers of online views and

engagements needed to justify my job.

Or anyone’s job, this marketer said. What do you

think this is, socialism?

The new reality? Newspaper executives wanted clicks.

Fuck public service, unless somehow there was a Pulitzer in

it, which would be a marvelous come-on the shrinking sales staff could bring to

certain advertisers. Well-endowed non-profits, for example. But not car

dealers, real-estate firms, floor and rug installers, hearing-aid

manufacturers, the Jitterbug cellphone company, and shyster companies promising

cures for erectile dysfunction, which remained among our biggest advertisers.

And me?

Maybe a feel-good piece every now and then that hints of

public service, for old times’ sake, this marketing moron said, but that’s

it. Maximize your clicks. You’re no dope. You can read the tea leaves. You

still like a paycheck, right, good buddy?

Good buddy my ass.

But I held my tongue.

As real newspapering continued to die, I knew the inside game

intimately. Not the time to shoot yourself in the foot. Definitely not the time

to proclaim Dana Priest, Seymour Hirsch, and Neil Sheehan as three of your

heroes.

So what was getting the clicks on that August 23, 2021?

Consider a few of the so-called “recommended” headlines and

accompanying stories — all from free-content providers — that were posted on

our website that day,

Go Topless Day Draws Hundreds, Even a Few Men

Desperate Housewives Without Makeup, the Shocking Reality

Giant Rabbit Hops Across Wyoming, Arrives Hungry in Idaho

Texas

Christian Has Proof She Walked on Water

She Hid

Under the Bed to Spy on Her Husband But Instantly Regretted It

Sultry

Country Star Steals Rival’s Diamond Necklace, Hides It in Her Cleavage

Man Buries

42 School Buses Underground. Look When He Reveals the Inside

The

Baddest Biker Girls in the World

We Can Determine Your Education Level in 25 Questions

Does Your Cat Throw Up Often? Try This One Trick

50 Photos That Show the Wrong Side of Cruise Ships

20 Hair Shapes That Make a Woman Over 60 Look 40

20 Southern Phrases Northerners Don’t Understand

17 People Who Learned the Hard Way

And there was no escaping these abominations.

They populated the home page from top to bottom and owned

its entire right side, and they popped up inside every second or third

paragraph of every story. Adblocking software couldn’t stop them. Rebooting and

clearing the cache couldn’t stop them. Clicking on the “X” next to the dread

AdChoices button in the upper right-hand corner couldn’t stop them.

You get the picture. A pathetic fucking picture. Not what I

signed on for those many years ago, when journalists believed journalism really

could change the world, not just line the pockets of newspaper executives and

owners.

But ordered by management to get the

clicks, I had “retooled my toolbox,” as the idiot marketer phrased it.

The result? I was now writing nonsense, three times a week,

except for July, when I vacationed on Block Island, where I fantasized I might

live someday as I wrote novels and screenplays.

Nonsense about socks, for example — 45 numbing inches about

losing socks in the washer, finding socks under sofas, socks without mates, the

amazing secret life of socks. I contemplated the greater meaning of winter

sunsets (OK, not bad), spring robins (also not bad), and Jell-O (shoot me now),

and I explored my separation from my wife, a columnist at DigBoston, Boston’s

leading website. Cue violins now, please. Or barf, your choice.

I recommend the latter.

Alliteration, adjectives, and clichés

had become my stock in trade, and I killed no darlings (see Faulkner, King, et.

al.).

If anyone needed further proof of how pathetic I’d become,

it could be found in how often I wrote about the difficulty of writing columns:

4.5 times a year, according to the smugly published calculation of my

soon-to-be ex-wife. Her math, sadly, was correct.

I took comfort knowing I wasn’t alone.

Our once-mighty newspaper — defender of truth, champion of

the common man, Pulitzer Prize winner, published every day since 1823 — through

wars, pandemics, depressions, civil strife, patriotic and idiotic presidents,

divided Congresses — was on the ropes, too.

Starting in the 1990s with the advent of the online era, The

Tribune’s daily circulation had tanked, from an Audit Bureau-certified

410,000 to less than 50,000 and still dropping. We couldn’t even stabilize our

flagship Sunday edition, which once had a circulation north of a million,

despite cutting the subscription price, lowering ad rates to peanuts, and

sponsoring online crossword contests with $5,000 cash prizes. Not sure if we

ever paid them, or just dangled that out there and followed up with excuses or

movie passes, but whatever, I digress. I do that a lot.

There were even rumors of moving to five-day-a-week

publication, or going entirely online — or even, in a worst-case scenario that

increasingly seemed possible, ending publication altogether, the presses after

two centuries silenced for good.

Had we been a two-rag town, by now we surely would have

become another ghost paper, run by a skeleton crew working remotely from Texas

or Indonesia.

But having bought and then folded The

Boston Chronicle, the only other print competition in the metro region, the

Trib owned a monopoly, which meant we had a new lease on life, for a spell

anyway. It meant we could hold advertisers hostage, to a degree.

It meant we still had some market value, which is why I was

not shocked by the events of that August morning, when I arrived at work to

find a remote-broadcast trailer with Florida plates in front of our building. A

satellite dish lifted toward the sky.

The Delta variant was ravaging the U.S. that summer, but we

were in Massachusetts, which had one of the highest vaccination rates in the

country. Nonetheless, fully vaccinated people — and that was all of our staff,

to the best of my knowledge — were required to wear masks indoors, and we were

working hybrid shifts, virtually from home on most days, with a rotating

schedule of only small numbers of us at the paper on select days of the week.

This was the first time we had been summoned to be on site

all together.

“Looks like the rumor was true,” said Destiny Carter, my best friend.

Destiny was one of The Trib’s long-time business writers and an African American, one of only three people of color on our staff. The others were photographer Erica Martinez, who was Hispanic, and Connie Lee, an Asian America. Critics who pointed to The Trib as a pillar of structural racism were right.

“You mean the rumor we were for sale?” I said.

“What else could it be?” Destiny said.

We were standing in the lobby with our good friend, reporter Bud Fuller. A film crew was loading tripods and cameras into the elevator to the fourth-floor auditorium.

“But Gordon vowed we weren’t for sale,” I said.

Just last week, in fact, publisher Randolph E. Gordon IV had issued a

written statement denying persistent rumors of a takeover.

“And two years ago he insisted we weren’t downsizing,” said Bud.

“His word means shit.”

Bud was right.

Three days after his written statement, Gordon slashed the staff by twenty-five percent, albeit through buyouts that left many of the remaining three-fourths jealous. For the record, that was the last of the buyouts.

What came next was good old-fashioned firings: a call to visit HR, where you were told you were terminated, your email and card key would be deactivated in a half hour, and you had until then to clear your stuff out and be off premises or security would be called.

“So, who’s the new owner?” I said.

“Must be SuperGoodMedia,” said Destiny. “It’s the only chain based

in Florida.”

My stomach churned.

“They’re worse than McClatchy,” I said.

“There’s something worse than McClatchy?" Destiny said.

“Hard to believe, but yes, and they’re it,” I said.