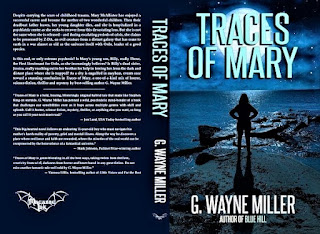

Herewith a short story -- free for the read -- that is set at a time of pandemic, with a twist of the extraterrestrial, one of the themes from my 20th book, "Traces of Mary," available in print, Kindle and audio editions. The reviews for "Traces" have been awesome!

THIS LITTLE BUG

This time, I walk.

I start early, emerging from my subway sleep nest by 5 a.m.

in order to greet the first commuters. So many busy people in the big city. So

many hard-working mothers and fathers. So many young people embarked on their

careers. So many big shots, major domos, people of substance and weight, the

movers and shakers of society here in and around Boston, Massachusetts.

You see, I walk.

I walk from the Park Street subway down Tremont to Chinatown,

then up Washington, past City Hall, through Quincy Marketplace to the

over-priced waterfront, back through the banking district and over to the

Common and Garden and Back Bay in time for the midday shoppers. At dinner time,

depending on the weather, I walk through the Prudential Center and Copley

Place. On occasion, I walk through the train and bus stations and over to

Boston Logan International Airport, where I comb my hair, walk erect, and act

on my best behavior, attracting little attention to myself.

All day and into the summer night, I walk.

I walk and I breathe—always breathing, deeply satisfying

breaths, in-out, in-out, in-out, with particular strength on the exhalation, a

refreshing vigorous breathing even though I allow myself a smoke every now and

then. When I breathe, I feel that familiar yet still-strange tickle in my

lungs, and I smile. I know it can’t hurt me, what’s been living patiently there

inside me.

So many thousands go by, an endless river, and I walk.

Some are still wearing their pandemic masks. Others, perhaps

fully vaccinated and believing they are immune to COVID but knowing nothing of

the far deadlier bug with which I am most intimately acquainted, revel in the

so-called freedom that going maskless allows after lockdowns and a year and a

half of hell.

Scum, they say, those that speak.

Swine.

Bum.

Get lost. Get a job. Get out of my way. Get bent. Yuck.

Gross. Fuck you.

There was a fleeting time early in the pandemic when the

public expressed empathy for me and my kind, dropping dollar bills at my feet

that I declined to accept and wishing me well. Or was that not empathy but

fear? Whatever, goodwill gave way to hostility as the vaccination rates rose,

hospitalizations and deaths declined, and Massachusetts opened up.

When you speak and cast evil eyes now, I do not answer.

But it makes me grin, knowing what I know, knowing that you

are completely ignorant.

Yes, I am a forbearing and extremely patient man.

It is good to be alive. In my own way, I am having a ball.

You may find that difficult to believe, looking at my clothing, my beard, the

shoes, the bundle I carry, but it is true. It is good to walk, to have that

occasional cigarette, to drink heartily from that bottle and enjoy. It is good

to be free, to have my health, such as it is, good to be able to breathe.

It is good to be alone.

It is good to be in the city, surrounded by so many.

I consider all of you my friends. I hate you with a passion

that does not abate, yet you are my friends. A paradox, you say. The world is

full of them. The sun that rises in the morning must sink in the evening. From

the dead of winter the springtime flowers. In the eye of a storm, the calm.

Paradox, my friends, the natural order of things.

Or are you so blind that you cannot see?

You will recall the childhood saying that sticks and stones

may break my bones, but words will never hurt me.

How true it is.

Your words roll off me, but your physical remonstrances

hurt, if not yet actually fractured bones. I have been beaten and mugged, by

young punks mostly. I have been chased, cornered, locked up overnight by the

cops. I have fought back, but in my own way and on my own terms.

Terms that are favorable only to me, as you shall soon discover.

I admit I am not a pretty sight. I do have plans to clean

things up.

Still, I know what I am, the nasty side of mankind still

living in caves. I myself lived cave-like once, in the not-too-distant past.

And yet, that is not the half of it.

Has it always been this way? you may silently ask

yourselves as you pass me by, disgust written on your faces and in the way you

cross streets to avoid me. You should know better than that. You with the

stylish clothes, the kids and the gas-guzzling SUVs, the 401(k)s and bank accounts,

the country clubs and Cape Cod and Berkshire weekends, and the neat, ordered

lives that are about to be ripped asunder in ways that will make COVID seem

like the common cold—you, my friends, should know better than that.

No one is always this way, or any way. Motion is inevitable,

the only constant being change. Didn’t Hegel teach us that? Marx and Darwin?

Everyone is born. Everyone crawls before walking, burbles before speaking,

scribbles before writing. Everyone loves, and in turn feels love, somewhere, no

matter how faint or brief or enduring. Everyone has a past, and there is good

in that past, and there is bad, too, not always in equal proportions.

I walk.

I walk because I want to be with you, because I have

something for you. I walk because of what you, fellow members of this species

called homo sapiens, have done for me. I want to pay you back.

Not necessary, you protest? What was due has been paid?

Oh, but I insist.

So I walk, always on the move. I walk into the crowded lobbies

of hotels and convention centers, and through the crowds outside Fenway Park.

Like the good people at the airport and the bus and train stations, they will

return home, whether home be Boston or California or England or India or China

or Japan or Australia. They will not know it, will never retrospectively trace

it back to me, but they will carry a lasting memory of a so-called homeless man

in Boston.

Let me tell you a little story.

I think there are things you should know, the next time you

encounter me and the stench of my breath, which you attribute, only partially

correctly, to cigarettes and booze.

The story begins, as many do, in the long-ago and far-away.

I was a much younger man then, a deeply respected man, if I may be immodest. I

was, in fact, a scientist, and I was called a doctor for the PhD I carried

after my name. Specifically, I was a climatologist, a widely published and

scientifically daring one, and my specialty was the conditions of weather and

astronomy that produce glaciers. My theories of orbital inclination (that is,

the changing angles with which the Earth over the millennia has faced the sun)

had revolutionized our basic understanding of the Ice Ages and I had recently

co-authored what was then the definitive text on the subject.

More recently, as carbon emissions rose and the planet warmed

and the ice caps began to melt, I established myself as an international

respected climate-change authority.

Therefore, I was honored, but not surprised, when I was

invited to join Polar 2020.

Chances are you have never heard of the Polar 2020 expedition.

There is no good reason that you should have. The pandemic ravaged the earth,

Trump was president, Biden hoped to beat him in the election, Putin still

blustered, and on and on and on. No, Polar 2020 rated only a small mention in a

wire story that ran in a few papers and websites and got no TV coverage that I

saw. But this bothered none of the scientists who formed our party, and I doubt

it made any difference to the seamen and officers who manned our ship, the RV Arctic

Maiden, either. Almost without exception, the most significant work in

science is conducted in methodical and decidedly non-romantic fashion, hardly

the stuff of front-page headlines.

Do not imagine, however, that this was your run-of-the-mill

scientific junket.

This was a multi-million-dollar effort, years in the

planning, supported by private funds and congressional grants, and it would be

many more years before our best universities and scholarly institutions would

sift and sort their way through the incredible wealth of data with which we

expected to return. Never had there been such a mission planned for the Arctic.

Byrd and Peary could only have dreamed of what we were determined to do. The

spectrum of interests was, perhaps, for a single mission, unique. There were

scientists with expertise in glaciation, zoology, ultraviolet radiation,

meteorology, geology, microbiology, internal medicine, immunology—yes, the

explorers themselves were to be subjects of unprecedented research. The

eventual result, we were confident, would be not only a deeper understanding of

the Arctic, but also of mankind itself as it faced its greatest peril in

recorded history.

Until, that is, what I am about to relate to you.

So, on an unusually hot day in late June 2020, we left Woods

Hole Oceanographic Institution. We departed without fanfare, only immediate

family members bidding us farewell. I kissed my wife and three teenage

children, promised to FaceTime regularly, and we were off.

Please forgive my immodesty, but everyone on that ship as it

sailed into Vineyard and Nantucket Sound and then the open Atlantic did have

great expectations. Personally, I, a fifty-two-year-old man, harbored dreams of

a Nobel Prize—or at least, finally, a nomination.

The irony of the day’s sultry weather presented did not

escape us.

In another week we were to be plunged into the northern extremes

of Greenland, that most misnamed of lands. True, it would be summer there when

we arrived, with daylight around the clock, and afternoon temperatures rising

well into the balmy 50s—but Arctic summers are notoriously short, as fleeting

and ultimately as disappointing as a former lover’s kiss, if I may be so

poetic. Within two months of our arrival, along toward the end of August, the

mercury would begin to plummet, the snow would begin, and we would be locked

into an Arctic winter—granted, one less harsh than in decades before. We

planned to stay almost a year, returning in May 2021, when the ice had released

what would then have become our captive ship.

From Woods Hole, we put in at St. John’s, then

continued on to Godthaab, Greenland, where we took on board a handful of Danish

scientists who were making the journey with us. From Godthaab, we steamed

north, along the shore of Baffin Island, where we observed the icebergs to be

multiplying in both number and size. We put in a day and a night in Thule, a

truly tiny and dreary outpost, then proceeded north again, until our captain

found suitable moorage in a fjord extending like a skeletal finger off Kane

Basin. The ice had grown even thicker, and the fog was nearly impenetrable at

times. We would safely go no further, our captain informed us, and there was

universal assent that Kane Basin suited our various needs to a T.

It took the better part of two days to unload our supplies

and equipment and establish our base camp on a sheet of rock overlooking a

glacier. Ours was not a geographical expedition, of course—the vastness of

Greenland by then had long since been charted and mapped—but an exercise in

information-gathering and experimentation that could, for the most part, be

conducted from a single camp. Naturally, there would be outcamps and selected

journeys inland, of two- or three-week’s duration. For these, we had along two

dozen Huskies and traditional Eskimo sleds—this at the insistence of our Danish

hosts who, for reasons we did not attempt to fathom, were soured on

snowmobiles.

The first weeks were a period of industry and good cheer

amongst our party, which had taken residence in a series of tents erected

behind the comparative shelter of a series of boulders. There is a certain

savage beauty to the Arctic summer, and that beauty, combined with the endless

day, was like a tonic. For it is summer when the wildflowers bloom, the

lemmings and ermine and arctic hare prowl, when whatever other limited flora

and fauna there is in this unforgiving territory explodes in crowning

celebration of the cycle of life. Then, too, there was the almost daily display

of aurora borealis, or northern lights, which paints its ghostly rainbow across

the sky like the backdrop to some haunted dream.

As for me, I was intent on rainfall collection, pollen analysis,

color spectrometry, ice coring—especially the latter. An entire history of

weather is captured in the layers of ice that comprise a glacier, and a simple

hand-auger-driven core, although time-consuming and sweat-inducing and

muscle-tiring, is worth its proverbial weight in gold. My colleagues were

plunged into their various and sundry labors, and there was the unspoken but

certain feeling that what we had successfully embarked upon was an expedition

bound for inclusion in the ranks of all-time great Arctic ventures, if such is

the way to describe a legacy that predates Eric the Red.

Winter’s arrival did nothing to disturb the

camaraderie that had developed amongst us. If anything, it served to strengthen

the bonds that had grown, and which now joined us together like the close-knit

family we had in fact become. The snow was virtually non-stop, as those of us

who were newcomers to this land had been told to anticipate. The wind was a

harsh master, and the temperatures were soon similarly uncooperative. By the

beginning of October, it was rare indeed the day when the mercury could be

coaxed above zero degrees Centigrade.

But it was not weather, or the onset of the Arctic night

(which, as you may know, lasts twenty-four hours a day) that began to change

the temperament of our party toward the beginning of January.

No, it was not that. Christmas had come, and we had

celebrated it with an evening of old-fashioned caroling and a rare dinner of

reindeer steak with gravy, a Danish custom on this largest of Denmark’s

islands. Those of us who so desired had Zoomed and FaceTimed with our families.

No, it was the discovery at Outcamp 3 that would eventually

bring ugly turmoil to Polar 2020.

Outcamp 3 had been set up some four kilometers inland by the

microbiology folks, who were in pursuit of various strains of bacteria known

only to this region and its equally inhospitable twin, Antarctica. It was

little more than a single tent, this particular outcamp, and it was not manned

on a continual basis, only as the dictates of microbiology demanded. Dave

Heddon was the head of the microbiology contingent, which numbered exactly

three, including Dave. He was a subdued man, introspective yet not glum, a

powerful, broad-shouldered father of two young boys who looked for all the

world like a starting NFL defensive lineman.

But he was a scientist—tops in his field, or so was the glow of

his reputation—and he possessed that deliberate and calm way of speaking, so

wonderfully rare, that is immediately soothing and almost therapeutic to those

who hear it.

And that’s how I knew something was up the evening of

January 24, when he returned from three days at Outcamp 3.

I was alone in the chow tent, finishing off a cup of

freeze-dried coffee, when Dave walked in, his beard twinkling with frost and

his boots glazed with ice. In place of that calm voice was an imposter, a voice

that fairly crackled with excitement. Remember, Dave Heddon was a man of

unusual emotional maturity and control. I had learned that listening to him

describe how much he missed his two young boys, but how sacrifices must

sometimes be made in the name of science—and now, now he was speaking like a

teenager high on weed.

“Out there,” he began, sipping on the steaming coffee I had

brought him, “I think we have discovered extraterrestrial life.”

“What?” I asked.

“What we found by Outcamp 3,” he said. “Frozen. And

perfectly preserved, or so it would appear.”

“What?” I repeated, persisting in my ignorance. “What have

you found?”

“Alien life. Twelve beings. From where, is anybody’s guess.

But definitely not of this world. You’ll know that as soon as you see their…

their heads.”

And then, his voice still tinged with excitement, he went on

to relate the events of the last two days at Outcamp 3. How he and one of his

party, Joanne White, had set off the first day to gather samples on the agar

plates they carried in special aluminum boxes. How they had wandered perhaps

200 meters north of the camp through an unusually strong, snowless wind when

they happened upon… shall I call them beings, as Dave did?… and the wreckage of

a vehicle they initially believed to be constructed of steel.

“We had reached the peak of a rise,” Dave recalled, “and

were descending the other side when our lights picked up what we first assumed

was another rise, albeit one irregularly contoured. Thinking little of it, we

moved closer, our lights stabbing the pitch. As we approached, the rise took on

a distinctly different shape. Or shapes, I should say, for there were several.

“The most prominent was a rockpile, roughly the size of a

large automobile. It looked as if it may have been erected, however crudely,

for purposes of shelter. Off to one side was a circle of blackened stones that

appeared to have once enclosed a fire. Moving closer still, we got our first

indistinct look at the… beings, four of them, sprawled in various contorted

postures around the stones.

“Of course, the term ‘beings’ had not occurred to us then.

Standing from the distance we were, and under such unsatisfactory light

conditions, we assumed we had found the remains of earlier human explorers—the

frozen cadavers of the unfortunate members of whatever ill-fated party it had

been. Many of the early European and American pioneers of this region, as you

know, never came home, and were never found.

“And who would have thought otherwise? The forms we were

surveying were of human size and appeared to have the human compliment of

limbs—two arms, two legs—and they were clothed in mammalian fur not the least

bit incongruous for this cruel environment. Arctic hare was my guess. Of the

four forms, no faces were visible. Not then. It seemed that their heads were

unusually large, but that was difficult to ascertain. They had died in the same

position, on their stomachs, faces into the snow.”

Dave stopped. He beckoned for more coffee and I willingly

obliged him. Never have I been so transfixed by a story as then.

“Wasn’t there a feeling of perturbation, observing such a

scene?” I said softly. “Even assuming, as you say you did, that they were early

explorers of this vast wasteland.”

“Indeed there was that feeling,” Dave continued. “I don’t

know how long we stood there, staring, contemplating, trying fervently to put

the pieces together, in all honesty more than a little scared. Ms. White and I

are microbiologists, Robert, as I need not remind you. Perhaps someone better

versed in anthropology or paleontology or medicine might have felt differently,

but we, frankly, were most uneasy standing there.

“After an indeterminate period—it probably was a matter of

mere minutes, although it seemed an eternity—Joanne and I moved closer. I think

we felt it simultaneously—the heat coming from that camp, if camp is indeed

what that place was for them. It wasn’t a suffocating, tropical heat, but the

zone surrounding the beings was several degrees warmer than the ambient

temperature. We could feel it on our faces.

“That’s when it occurred to me how unusual it was that snow

had not drifted over the whole site. Obviously, the heat, whatever its origin,

had been sufficient to keep the site clear. Protected, as it were, from the

elements for a period of time.

“By this point, neither Joanne nor I were talking. This

feeling of perturbation you have alluded to was beginning to intensify. Even

before we turned one of them over to look at a face, we both knew something

about this site was terribly strange. And I don’t mean the fact that death had

visited. Certainly, that was gruesome. But this feeling—by the second, it grew

stronger. Not fear exactly. No, it was closer to the sort of nervous excitement

I imagine Howard Carter felt on first entering Tutankhamen’s burial vault.”

There was a pause.

“I see by your look I’m having difficulty conveying those

feelings,” Dave said.

“Hardly,” I said. “You are doing an admirable job.”

“Naturally, our curiosity was too much to contain. Just as

Carter could not control the urge to gaze upon Tutankhamen’s visage, neither

could we curtail our desire to see the faces of these… at that point, we still

believed they were human, you understand. Having some scant knowledge of

earlier discoveries of camps, I believed it was possible that we would see a

perfectly preserved face. Pained and having suffered, no doubt, but preserved

in a condition allowing transport to a more appropriate final resting place—a

family cemetery, for example.

“We moved to within inches of one of them. We could see then

that its head was much larger than it should have been, but we were too rattled

to dwell on that incongruity. It took both of us to roll that one over. The

body itself was frozen solid, of course, and it was heavy, and the job was

complicated by the poor light. Finally, after trying various positions and

leverages, we managed to turn it onto its back. I had placed my flashlight down

to free both hands, so it was Joanne who first illuminated the face.

“I was sure I would faint. My knees went weak. For instead

of the human face I had been expecting, there was something one only encounters

in nightmares. There was no forehead, no nose, no ears—only a single eye, the

compound eye of an insect such as the common dragonfly, grossly exaggerated in

size. Worse, it seemed as if that eye were still experiencing vision.”

“Dear God!” I exclaimed.

“I say that because there was a purplish iridescence

emanating from that eye. But it was not a constant color or intensity of color,

far from it. For the few seconds we stared at it, it seemed to be changing hue,

from purple to blue to yellow—to be pulsating, as if it were electrically

charged, or had been irradiated, or was radioactive. Almost like—like it could

still see us, whatever it was. Naturally, it couldn’t, but that was the

overwhelming impression.”

Suddenly, I was cold. I drew my coat closer around me, to

negligible effect.

“I know how all of this must sound,” Dave continued, “like a

script to a Hollywood movie, but you and everyone else will have the

opportunity to see for yourselves, I am sure. I assume every effort will be

made to recover all four beings.”

“You assume correctly,” I said. An incredible discovery such

as this could only lead to intense study and investigation.

I noticed that Dave was tapping his fingers, as if still

trying to fully comprehend what he had seen, without great success.

“Where was I?” he finally said.

“You were describing the face.”

“Yes, the face. After seeing that, there ensued another

period of near-complete silence—nothing but the wind, and the whistling noise

it made passing over the rocks. Joanne looked at me and I returned her look,

but we said nothing. I am sure you are wondering if I was frightened. In fact,

I was, I will admit—but only to a minor degree. Because despite whatever low

level of energy remained active within its eye, which presumably was its nerve

center, I was convinced it was dead. Frozen, probably for years, possibly for

decades, there seemed no way it could have survived.

“So it is understandable that after our initial surprise

began to fade, we succumbed to curiosity. From being to being we went, turning

each of the four over, examining each, taking mental notes. As near as we could

determine, they were identical—the same approximate size, same number of limbs,

same compound eye. If, indeed, there were differences of gender or age, they

were not discernible from our inspection.

“It was not until after we had examined each of the beings

that we happened upon the vehicle. It was secluded on the far side of the rock

pile, deliberately, I suspect, to protect it from wind and storms. It would not

surprise me to learn that the pile was erected specifically to protect it from

the elements in the hope, one might guess, that it might someday be repaired

for a return trip home.

“By that point, a hypothesis was beginning to emerge.

Namely, that these beings, whoever they were and wherever they were from, had

been stranded there by accident or mishap or mechanical malfunction—and maybe

by something as simple as running out of fuel. Quite conceivably, they were

awaiting a rescue mission that never happened. That would explain why they had

built their camp, and why they had died in it. It would explain how they had come

to hunt the arctic hare whose fur they made into the coats they were wearing

when death overcame them. And it would explain the fires they burned from the

few scraps of vegetation they had been able to forage back toward the coast.

Because no matter how technologically advanced they were, I was convinced that

they were warm-blooded creatures dependent on the interior environment that was

their means of transportation. Once that was lost to them, it was only a

question of time before they—so fragile as they must have been—succumbed to the

elements. Particularly if they were stranded here in the dead of winter, as is

my strong suspicion.

“In any event, we found the vehicle—or what I suppose is their

vehicle until proved otherwise. If you have ever watched certain movies or TV

shows, you may have some conception of what a so-called spaceship is supposed

to look like: shaped like a cigar or a pie, large in size. This is nothing like

that. To begin, it is in the shape of a perfect cube. It is small, about seven

feet per side, with a seating arrangement that maximized all available space, I

suspect the four could fit inside with little difficulty. Based on our cursory

look, I would hazard that it is made of stainless steel or some steel-like

material manufactured in the place they come from. There are no markings, no

lights, no windows or portholes, and only the outline of a door. I think other

members of our team will be tempted to open it once we have retrieved it—that

is, if salvage is feasible with the equipment we have.”

The remainder of Dave’s account chronicled how he and

his colleague had spent another hour at the site, probing and sifting through

the snow for other artifacts. Strangely, there were none, none that could be

found, anyway—no tools, no lights, no sleeping bags or tents, no food supplies,

no utensils or scraps that would indicate food had ever been prepared or eaten

at the site. In fact, Dave recounted, the entrails and meat of the hares they

had made into coats had been left untouched. These findings, he noted,

reinforced his hypothesis that they were fragile beings—beings that perhaps

were unable to eat the kind of food available in this sparse environment, if

they ate at all and didn’t subsist on some form of energy unknown to us. Beings

that were of a higher order, unquestionably—but beings ill-equipped to handle

Arctic cold.

Seeing that their battery power was running low and

recognizing that their original mission of collecting microbiological samples

was still incomplete, Dave and Joanne left the site—but not before determining

to their mutual satisfaction that they would be able to find it again.

“Truly, it’s an awesome discovery,” I said when Dave was

done.

“I think you understate the case,” he said, with a smile.

“Next to this, King Tutankhamun would be but a sideshow in the long history of

discoveries. Think of it, Robert! Extraterrestrial life, perfectly preserved!

Along with the vehicle in which they traversed the universe. There’s simply no

telling how this could revolutionize any number of fields. Aeronautics.

Physics. Biology. I could go on. It will be years before the full impact of

this is understood and implemented!”

Needless to say, word of the discovery spread through the main

camp in no time.

A meeting was convened the next morning,

and all but a handful of our party was in attendance. After allowing Dave and

Joanne to retell their story, attention turned to the logistics of retrieving

the beings and their vehicle. A crew would leave that afternoon to do the

preliminary work, and the hope was that the beings could be brought to base

camp the next day, with the vehicle to follow within a week—the latter

timetable depending, of course, on its weight, the difficulty of building a

suitable contrivance to move it, and the power of the Danes’ trusted Huskies,

which had proven themselves all winter in whatever tasks had been put to them.

It was further agreed that a special tent would be erected solely for the

purpose of studying the beings. A separate tent would house the vehicle.

As it developed, recovering the beings and their

vehicle took only a few hours, and we had everything safely in camp by dinner

the following day. The explanation for this unanticipated expediency was at

once simple but baffling: the vehicle, which we had assumed weighed tons,

actually weighed less. In fact, much to the amazement of our mechanical crew,

we found that three of us could lift it, and a single Huskie could haul it once

it had been secured to a sled. Whatever alloy had gone into its construction, it

was not iron or aluminum or steel—or any material known to mankind, for that

matter, as subsequent tests would reveal.

Almost immediately, the physicians, led by Dr. Bruce C.

Hazlett, the expedition’s surgeon and medical chairman, began their autopsies.

They worked virtually around the clock, fueled, as they were, by the same

adrenalin coursing through all of us. They were meticulous in their work, for

they well knew that a legion of scientists back in the States would want their

own opportunities for research once we had returned with our find. It was slow

work, painstakingly documented by extensive notetaking, videotaping, and

photography, but by the end of the first week the doctors had learned a

tremendous amount—and had been confronted with an equally impressive number of

mysteries and inconsistencies.

Dr. Hazlett’s team discovered, for example, that the beings’

skin was similar to human skin, having the same number of layers and composed

of cells similar in structure and apparently serving the same functions—protection

from infection, regulation of internal temperature, retention of vital fluids.

Our medical staff was able to document the muscles, ligaments, and skeleton,

all of which suggested the beings had walked in an upright manner. There were

no toes on the feet, and no hair on their heads or anywhere else on their

bodies, but as one member of our party noted, those features are already all

but vestigial in homo sapiens itself.

I suppose none of us were surprised to learn that Alpha,

Beta, Kappa, and Epsilon, as we had taken to calling them, possessed brains

nearly twice the size of their human counterparts. Their spines, too, were

approximately double human size, with a capacity for twice the volume of

nervous tissue. As for the eyes—those haunting eyes, which none save the

doctors chose to look directly into for very long—they were indeed the source

of radiation, of an intensity, fortunately, that was too low to be of danger to

us. Its purpose, however, remained an open question, one that we on Polar 2020

could answer. That would require more advanced technology and specialists we

did not have on board.

And so that question and many besides were left to

subsequent endeavors.

What did they eat? A particularly vexing puzzle, for there

was no stomach or intestines. Did they eat at all, or exist on some non-organic

form of energy? Did they speak, or was communication accomplished in some far

more sophisticated mode, as we suspected? They indeed had mouths and tongues,

but the muscles of the tongue, the doctors concluded, were only crudely

developed, and where vocal cords should have been there was nothing. How did

they reproduce? There was no evidence of sex organs and no indication of

differences between the genders—if, in fact, two genders were represented.

Alpha, Beta, Kappa, and Epsilon were carbon copies of each

other, or so it seemed.

Our technicians were unsuccessful in their efforts to

penetrate the quartet’s vehicle, for it resisted all attempts to puncture,

drill, pry, or bang open. Unquestionably, their vehicle held clues as to the

origin and nature of the beings—and what quantum leaps in technology might be

possible after the vehicle’s secrets we could only guess. It was not too wild

to dare to believe that the vehicle might even provide useful to our nation in

keeping the edge in the new arms race developing between the U.S. and China.

Alas, those exciting developments were destined to wait until

later.

The weeks passed and the excitement over

Alpha, Beta, Kappa, and Epsilon subsided. Spring was approaching, and although

in that clime spring promises only the return of weak sunlight and temperatures

only occasionally above freezing, something that could legitimately be called

spring fever had us in our grip. Even excepting our alien finds—they themselves

were destined to make the name Polar 2020 a household word, I was confident—our

expedition had been a tremendous success, more so than anyone had dreamed

during the months of planning preceding it. My own endeavors had borne fruit

beyond my expectations, and with no small measure of pride in my achievements,

I looked forward to authoring and co-authoring several major papers upon my

return to the halls of academia.

It was the last week of April, nearly a month before

we had planned to depart Greenland, that Dave and Joanne became sick.

Curiously, they both took ill the same day, and at

approximately the same hour, late morning. But beyond that coincidence, nothing

about their initial complaints raised an eyebrow. Without exception, all of us

experienced sickness since our arrival on the island—and Joanne’s and Dave’s

symptoms matched those of the flu that had spread through the camp earlier in

the year. Headache, stomach cramps, fever, annoying cases of diarrhea—yes,

their symptoms fit those of an ordinary viral infection. Seeing that their

business was microbes, I, for one, simply assumed that Dave and Joanne had

contracted their bugs in the course of their work.

By the third day, it was becoming clear that their malady

was not commonplace. Instead of improving, or moderating, or at the very least

stabilizing, their conditions had worsened. Their fevers had intensified, and

with temperatures threatening to break 107 degrees, they had started to have

auditory and visual hallucinations. Had we been in an equatorial zone and not

an arctic one, Dr. Hazlett said, there would have been a suspicion of malaria.

But malaria was not their diagnosis, nor could the doctors come up with one

that satisfied them.

What was most disturbing was that their sickness did not

respond to antibiotics or any of the other treatments the doctors tried.

At 10:25 p.m. on May 2, after having lapsed into a fevered

frenzy that had forced us to bind his ankles and wrists and strap him to a

stretcher in the camp’s sick bay, Dave died of heart failure. Three hours

later, in the early part of May 3, and following a similar period of extreme

agitation, Joanne also succumbed. Their deaths plunged us into severe

depression. Everyone had been following the course of Dave’s and Joanne’s

health, particularly in their last three or four days, and the knowledge that

they were gone devastated us.

What was even more chilling were the fevers a handful of

others were beginning to report even as Dave and Joanne lay on their deathbeds.

By May 6, nearly half the camp was experiencing the same

symptoms. Whatever the cause, we were witnessing an epidemic we could not

curtail. That was indisputable. During an emergency meeting of the remaining

healthy crew, it was decided that Polar 2020 must be immediately terminated and

we would return to the U.S., more than two months ahead of schedule. In the

time it would take to break camp, the sick were to be quarantined and the

healthy were to take rigid precautions in the handling of food and water.

Six more expeditioners—I need not name them—had died by the

morning we pulled anchor and steamed back out through the ice-clogged waters of

Kane Basin. Like Dave and Joanne, the bodies of the deceased were placed in

refrigerated storage on the Arctic Maiden for the journey to home and

proper burial. Autopsies, of course, had been performed on Dave and Joanne, and

they were performed on the next six, as well. The manner of death in every

case, Dr. Hazlett reported, was heart failure induced by prolonged fever and

dehydration. As to the cause of the fevers—that was surmised to be viral in

nature, although Polar 2020 lacked the expertise and technology needed to

isolate or positively identify the villain virus.

I was hardly the only person as yet unaffected by the

disease who began to believe that its advent must be associated with the

discovery of the beings—who, ironically, were being kept in the same cold

storage as the human dead for the trip south.

True, our first contact with them had been three months

before the onset of Dave and Joanne’s distress. But as those two scientists

themselves would have been quick to observe, some microbes have an incubation

period in humans of weeks or months or even years—consider syphilis, as only

one example among many, whose tertiary effects may be delayed as long as three

decades after contact. Perhaps the beings had not been overcome by cold, after

all, I thought; perhaps it had been a virus, one they had brought with them, or

been infected with on their arrival here. If so, that virus had remained

inactive, but lethally alive, in Greenland’s cold.

As might be imagined, we were in regular contact with the

authorities during our trip south from Greenland. Our situation, from what I

could gather talking to the captain and Dr. Hazlett, was being monitored with

growing concern in certain circles in Washington. By the time we had reached

the northern coast of Maine, plans had been formulated for a Navy helicopter to

fly several of the government’s infectious disease specialists out to our ship

for an on-site inspection.

We did not blink at this announcement. Naturally, it would

be necessary to take the proper steps to ensure our arrival would not

contaminate the population at large. These specialists would assist in the

planning, we assumed, and no doubt would take tissue and fluid specimens from

the shipboard autopsies so as to commence their own investigation without

further delay.

Just after noon on May 11, the helicopter touched down on a

makeshift flight deck the crew had cleared by rearranging some of the equipment

and booms aft of the pilothouse. I was unnerved by who disembarked: men dressed

in Hazmat suits and breathing from air tanks on their backs. More disturbing

still was what they carried: not equipment for collecting specimens, but

military-issue M249 light machine guns. I asked one man why it was necessary to

be armed, and he replied that this team by regulation was routinely armed,

whether on a friendly mission such as ours, or on a Specials Forces mission in

some war.

The men in white spoke briefly with the captain and Dr.

Hazlett, then were led below to where the bodies were being stored. In less

than five minutes, they returned, but not empty-handed. With the help of

several of our crew members, the men in white had brought topside the bodies of

the beings, wrapped tightly in canvas. They also carried steel canisters

containing autopsy specimens from our human victims. It took little time to

load them into the cargo bin of the helicopter, which had kept its door sealed while

the beings had been brought up. Next, a line was attached from the helicopter

to the space vehicle, which we had encircled with cable and lashed to the deck.

Before we knew it, the helicopter was gone—and with it, Alpha,

Beta, Kappa, Epsilon, and their vehicle.

At dawn the day after the helicopter visit, a U.S.

Navy frigate appeared on the horizon and broadcast a brief radio message

ordering us to remain at our present position, some seventy miles due east of

Jonesport, Maine, until further notice. The frigate, the USS Sam Houston,

then steamed approximately two miles upwind of the Arctic Maiden, where

it took up a watch it was careful to maintain. Like the Arctic Maiden, Sam

Houston’s captain informed our own skipper that the frigate was to remain

in the area awaiting further word from the authorities as to the time, place,

and manner of our return home.

Our instructions by now were originating in the highest levels

of the Biden Administration, which we learned had mobilized a crisis team of epidemiologists

and public health experts led by Anthony Fauci. The number-one concern, of

course, was the public-health threat we represented—concern about a possible

pandemic on top of a pandemic—and while we on the Arctic Maiden were

becoming increasingly panicked about our own fate, I think even the sickest

among us could appreciate the administration’s grave concern. Although we were

not privy to the details of deliberations concerning us, this much was conveyed

to us through the Sam Houston: arrangements were being made to

quarantine the remaining members of our party in abandoned barracks at the old

Brunswick Naval Air Station, north of Portland, Maine.

A week we waited, conditions on board the Arctic

Maiden deteriorating almost by the minute. There was one other helicopter

visit—to drop supplies of morphine sulfate requested by Dr. Hazlett to ease the

discomfort of our most seriously ill—but otherwise we were as disconnected from

civilization as we had been in Greenland. It was during this week that morale

disintegrated. It was during this week that six more died, and all but two of

us began to show at least the beginning symptoms of the disease—the two being

Dr. Hazlett and myself.

In their fevered states, the survivors took to wandering the

ship, talking to themselves, gesticulating at imaginary foes, uttering

vituperative and profane language, accusing their colleagues of the most

reprehensible behaviors. Of a more frightening magnitude were the altercations

that spontaneously began to erupt among the crew and the scientists. The word

nightmare does not adequately describe this week, and I spent much of it

together with Dr. Hazlett barricaded inside my cabin, venturing out only to

procure food.

On the seventh day, those few sailors who had stayed faithful

to their posts abandoned them. Until then, they had managed to maneuver the

ship so it stayed roughly within the two-mile radius allowed by the Sam

Houston. On the seventh day, they shut down the engines, locked their

hysterical captain into his wardroom, and left the ship to drift. A group of

five then took to a lifeboat, lowered themselves into the water, and headed off

in a westerly direction.

A storm was brewing but they had traveled a distance when the Sam

Houston fired a missile that sank them.

So you’d like to know what happened next, wouldn’t

you? You people who scorn me now as I walk among you, inhaling and exhaling

deeply, this most highly transmissible of all germs I carry spreading widely,

then doing what it is programmed to do: replicate and kill.

Long story short, I saw the explosion that sank the lifeboat

and knew what was next. In a sort of modern take on the Titanic, I

lowered myself off the ship into another lifeboat moments later. I had barely

moved to safety when the Sam Houston sank our ship with a second

missile.

The storm intensified soon after, which may explain why the

Houston could not find me. Or perhaps the captain concluded no one could

survive such a storm—a true Nor’easter that sent several vessels larger than a

rubber-hulled dinghy to the bottom—and never initiated a search. Whatever, I am

sure there was an investigation. That captain’s stripes, I bet, have been

stripped.

In any event, miraculously I did survive the storm. For

several days I drifted, until the lifeboat came ashore at Bar Harbor, Maine,

where I broke into a car whose owner, apparently a forgetful sort, had left her

pocketbook in view. I stole her cash, enough for the bus trip back to Cape Cod

with plenty left over for the inevitable contingencies.

I had hoped my wife and children would be ecstatic when I

reached my home, but they were anything but. Federal agents had prepared for

every possibility, even the one-in-a-million chance that I or someone else had

survived the sinking of the Arctic Maiden. Families, friends, and

colleagues had been instructed to call if anyone showed up. Police patrolled.

“I’m sorry, honey, I have no choice,” my wife said, closing

the door.

I was about to plead with her when I heard sirens.

More days and bus rides brought me to Boston, the nearest

big city. Easier to hide there, not that I would be easily recognizable now,

given how long I had gone without a shave or haircut, or even a shower or

change of clothing. I place no trust in homeless centers, however

well-intentioned their operators may be.

Let me leave you with a few facts and questions for you to

ponder.

The questions first.

Did Alpha, Beta, Kappa, and Epsilon know what they carried?

Clearly, they were immune, but did they know? If they did, were they on a

mission to destroy a species they held, correctly, to be a threat to Planet

Earth—and, with Bezos and Branson and NASA seeking to colonize space, planets,

and systems beyond? If they did not, why had they come?

Ultimately, these are esoteric questions. What happened,

happened. What is, is.

Now, the facts.

Unlike the coronavirus, this one spreads equally well

indoors or out. Thrives in all temperatures, from sub-freezing to extreme

climate-change hot. Requires an almost infinitesimally low virus load and

overwhelms the immune system quickly. To the researchers, I say: good luck with

your vaccines. Pfizer and Moderna got their COVID products in months, but you

won’t even have weeks with this particular bug. Even if big pharma did, what is

the guarantee they could succeed? This one came from far beyond. I would be

surprised if the laws of our science applied.

By the way, good luck Fauci and CDC and FDA and WHO.

In my lighter moments, I imagine this virus rejoices,

for stripped to its essentials, what is the purpose of any life form but to

reproduce, in this case to propagate its RNA so that it sees another tomorrow.

Shall we give it a name? SuperCOVID? The media types would

love that, in the brief period before the Apocalypse. COVID-Ultimate? Alien

variant? Shall there be a national naming contest before time runs out?

Or how about a reality show! The Virus is Right, say.

American Virus. Dire Jeopardy. Dancing with the Extraterrestrials.

Ha-ha.

Lol.

It is important that I maintain a sense of humor.

And keep things in perspective.

Because while this little bug has arguably made me a tad

daffy, it cannot kill me, for I am lucky to have developed immunity. The

scientist in me knows I belong to a very small cohort—that .000001 or less

percent who will survive as our species largely departs the planet, leaving it

to heal from the wars and industrialization and hatred and anger that so plague

it.

How will I subsist, you may rightly ask?

As I do already: with food from dumpsters. As the population

plummets, I will find sustenance from the food left behind in stores and

warehouses. Canned goods have a shelf life measured in years. And after that, I

shall partake of Mother Earth’s bounty, the berries and grains and fish and

wildlife that sustained our ancestors eons ago.

Yes, I will be fine.

I may even, should opportunity arise, decide to procreate.

When it comes to ensuring safety and hygiene, choosing the right surgical gown in Australia is essential. Our premium collection of surgical gowns offers exceptional protection for medical professionals. Designed to meet the highest standards, these gowns provide comfort and durability during long hours in clinical environments.

ReplyDeleteWhether you need Surgical Gown Australia for routine procedures or specialized operations, our products are crafted with breathable, fluid-resistant materials to keep you safe and comfortable. From hospitals to clinics, our surgical gowns are trusted by healthcare providers across Australia.

Explore our range of high-quality gowns, ensuring protection without compromising on mobility. With strict compliance to Australian safety guidelines, our surgical gowns are a reliable choice for all medical environments. Choose us for premium surgical gown Australia solutions tailored to meet your needs.