|

| Potter's field, Spring 2016: State Institution Cemetery No. 2, Cranston, Rhode Island. |

Early in my career as a staff writer at The Providence Journal, I covered two of Rhode Island's public institutions where many of the state's most vulnerable people lived: The Ladd Center, in Exeter, for the developmentally and intellectually disabled; and the Institute of Mental Health, in Cranston, for people living with mental illness. By the mid-20th century, both had become degrading and dehumanizing warehouses rife with cruelty and abuse. Following years of lawsuits, Providence Journal exposés, and tireless advocacy by heroic people, they closed in the 1990s after some latter-year improvements. A model community system, since deteriorated, had been built.

|

| 'The inertia of despair.' Providence Journal exposé, 1950s. |

With the death of the developmentally disabled 70-year-old Barbara A. Annis in February 2016, allegedly following staff abuse in the state-run group home in Providence where she lived, Ladd recently has been much in my thoughts. I penned some of them, along with the story I wrote on Ladd's final day -- the day the declaration "the beast is dead" was made -- in an earlier post.

Thoughts of Ladd have prompted reflection on the Institute of Mental Health, or IMH, previously known as the State Hospital For Mental Diseases, and before that, the State Hospital for the Insane (the State Asylum for the Incurable Insane was proposed even earlier).

|

| State Hospital for the Insane, early 1900s. Overcrowded, hundreds of patients slept on the floors. |

|

| IMH, 1950s. |

As with Ladd, thousands of people disappeared virtually without trace behind the brick and granite walls of that institution; I told the story of one of them, Hope Lincoln, in an extensively researched story for The Journal. And during those closing days of the IMH, I spent many hours at the institution, including living there for a week to chronicle in print what were then-improving conditions and even marching on several occasions with patients and staff in the annual Field Day, a vestige of the 19th century, when "inmates" were let outside (under close guard) for a parade and festive food. Below you will find three of my stories about three such Field Days.

For many of these people, particularly in the 1800s and the first six or seven decades of the 20th century, Field Day was the only time they ever got out -- until they died. Those few who still had connections to relatives might be sent for dignified burial in a church or community cemetery. But the majority, like Hope Lincoln, had no relatives that cared or even knew of them and got no such respect. Shame and stigma ruled -- and, sadly, still do today, albeit to a lessening extent.

They were buried in potter's fields, under concrete markers with sequential numbers but no names, the final -- and in most cases, only -- evidence these human beings had ever existed. I visited one of the IMH potter's fields early in my coverage of the institution, and it haunted me -- and has, on some level, ever since. The potter's field similarly affected my friend Dan Barry, New York Times staff writer, who last year wrote so eloquently of another potter's field and the man who buried the dead there in one of his This Land columns: "Restoring Lost Names, Recapturing Lost Dignity."

A few days ago, I revisited Rhode Island's State Institution Cemetery No. 2, as the old IMH potter's field is now called (even today, numbers, not names, attach to the forgotten dead). It was a pristine spring morning: trees budding, birds singing, temperatures rising, the sun sparkling on the Pawtuxet River, which winds toward Narragansett Bay. Over the years, an adjacent landfill has further encroached, providing another sad irony: people who in life were considered little better than trash in death now lie next to the real thing. Still, the field, tended by state-prison inmates, was trimmed and green. And except for the birds, it was quiet.

As I walked the field, I found that time has been unkind: some markers have worn away; others are toppled or gone altogether, the work of vandals. I wondered who had left the sole decoration, a plastic floral arrangement next to marker 1,142. Did they know who was buried there? What was their relationship? Or was this a random act of respect? Like the identities of the dead, I will never know.

|

| Marker No. 1,142. |

I counted 632 numbered markers: 632 people who died just from 1933 to 1940 alone at "the state institutions": the IMH and other facilities at the Howard complex, home also to the state prison, the state training school, and the state infirmary, predecessor to today's Eleanor Slater Hospital. Untold thousands of residents of those institutions and the long-closed State Farm for the poor from earlier and later years are buried in other potter's fields. In an ultimate form of indignity, the state simply paved over one of them -- the State Farm Cemetery, which had an estimated 3,000 graves dug from about 1873 to 1918 -- when it was building Route 37. I suspect few people driving on that busy thoroughfare have no idea what lies beneath them as they travel.

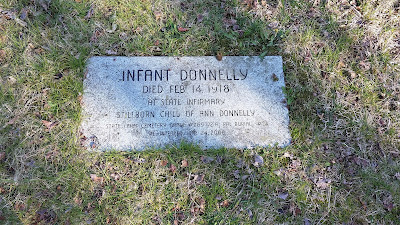

Heavy rains in 2006 washed out the remains of 71 of those State Farm residents near Route 37, and archaeologists were able to at least minimally identify most of them, including Infant Donnelly, the stillborn child of State Infirmary resident Ann Donnelly, about whom nothing else is known, either. Infant Donnelly died on Valentine's Day, 1918. More on the Route 37 story at the end of this post.

|

| Infant Donnelly. |

Like Infant Donnelly, the 70 other individuals are remembered with flat stones. A handful of remains are unidentified; some of those, having thwarted the archaeologists, are labeled "co-mingled." But there is Elizabeth "Lizzie" Anderton, daughter of James Gregson and Lucy Sielding, circa 1840 - Oct. 20, 1916; and Dinah "Maria" Cleary, wife of Patrick Cleary, daughter of Thomas and Margaret Finnegan, circa 1845 - Sept. 7, 1887; and John Gurney, a.k.a. Gierney, husband of Bridget Myers, circa 1841 - Dec. 21, 1873; and Manoog Shegdian, husband of Saonik Shekoian, circa 1868 - Oct. 21, 1916; and more, an apparent mix of working-class ethnicities and races. The wealthy had their private hospitals, and their respectful final rites of passage and resting places.

|

| Elizabeth "Lizzie" Anderton, et. al. |

Standing there, I imagined their lives: their days, interminably long; their nights, surely restless; the weeks stretching to months and then years and then decades, memories of the outside world fading, except, perhaps, the faint one of childhood joy, before the onset of their illnesses... a reminder of what might have been, and what was for lucky others who remained mentally healthy. The dream of ever leaving, except the final trip to the potters field, receding... or did some keep that dream alive? I thought of One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest: the extraordinary final scene, one of the best movie endings ever, when Chief Bromden hurls the hydrotherapy console through the window and escapes.

|

| The final scene of One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest. |

The drudgery and isolation were but part of it. Unquestionably, there were good and caring staff who sought to ameliorate suffering and practiced a degree of sound medicine, but there were also abusive workers and barbaric treatments.

For example, the lobotomy: the surgical separation of the lobes of the brain, the debilitating and personality-erasing operation that prompted Chief Bromden in Cuckoo's Nest to smother Randle Patrick McMurphy, played by Jack Nicholson, after he was lobotomized. Astonishingly from today's perspective, at least, the inventor of the lobotomy, Portuguese neurologist Egas Moniz, won the 1949 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

There was the even more horrifying hempispherectomy, in which one half of the brain was entirely removed.

There was hydrotherapy: captive immersion in warm (or cold) baths for hours or even days, and the "shower" treatment, in which patients, strapped into chairs, were sprayed with jets of water. Picture waterboarding.

And shackles and restraints, and isolation chambers.

|

| Isolation. IMH, 1950s. |

And the administration of the toxic substances chloroform and potassium bromide, and the forced use of morphine and alcohol -- alcohol!

Some patients were injected with malaria-infected blood to produce fever, which supposedly had curative power.

Others were subjected to various forms of shock therapy. One form, to treat schizophrenia, involved the injection of insulin to induce coma and seizure. The quack Dr. Manfred Sakel, who introduced insulin shock therapy in 1933, wrote that "the convulsions and comas of the deep shock brought about dramatic psychological changes in the patient. . .the indications were rather that the physiological shock restored the homeostasis in the nerve cell by forcing it to mobilizing its defence reactions, thus causing a restoration of the balance in the automatic nervous system."

|

| IMH, 1970s. |

And on the crazy belief that "damaged" or "displaced" parts of the female reproductive anatomy were related to insanity, some mentally ill women were forced to undergo "female surgeries." One practitioner, London's Dr. R. Maurice Bucke, wrote of 106 operations between 1895 and 1898. He claimed that 71 of the women "either recovered their mental health or this was improved." Among the specific operations, according to the "Restoring Perspective: Life and Treatment at the London Asylum" project: "Sixteen hysterectomies, 12 removals of diseased ovaries and tubes, 22 operations involving the replacing and retaining of the uterus in the normal position, 30 operations on the cervix, 21 minor uterine diseases, and 8 operations for vaginal lesions."

A virtual tour through all of these now mostly long-discontinued treatments can be found at the "Restoring Perspective" project.

In fairness, treatment for severe mental illness before the advent of psychopharmaceuticals (which are not without side effect, and which hardly constitute a cure-all) was vexsome; intractable diseases, like severe schizophrenia, defied any treatment. Still, well-intentioned efforts competed with the broader mandate of control and containment. Like Hope Lincoln, many who were committed for life had only experienced non-debilitating anxiety, depression or other conditions; or were homeless or impoverished; or acted only "oddly," in the eyes of a judgmental world; or crossed the police or a judge or another authority; or were sexually promiscuous; or otherwise deemed a "nuisance" to the community.

With records lost or gone, identities rendered anonymous, and buildings closed or razed, about all that is left of these countless untold stories -- each, the story of a unique human life -- are sequentially numbered markers in potter's fields and bones beneath.

We must never forget the forgotten, nor the larger story that is told through them: man's inhumanity to man, a never-ending tale that, we can only hope, one day will cease to be written.

|

| Another view of the IMH potter's field, aka State Institution Cemetery No. 2. |

|

| State Institution Cemetery No. 2 stone. Note SIC No. 3, nearby, re-burial site for 577 others. |

FIELD DAY STORIES:

Troubles and cares are forgotten as patients at state institutions enjoy their glorious Field Day

G. WAYNE MILLER

Publication Date: May 24, 1985 Page: C-09 Section: NEWS Edition: ALL

Field Day, 1985, for the state-run General Hospital and the Institute of Mental Health, and the institutional grounds have become a sprawling carnival.

It is one of Rhode Island's older and most colorful traditions, this annual production known as Field Day, and yesterday's version had what they've all had going back over the years - a parade, music, good food, games, prizes, a feeling that for one day, at least, the world can be something more than a ward.

The parade included fire engines of three different colors, a marching band, high school cheerleaders, clowns, floats, a motor scooter, a bicycle, Santa Claus on roller skates, Fred Flintstone on a truck, a gaggle of bureaucrats from the state Department of Mental Health, Retardation and Hospitals, which runs both institutions.

THE PATIENTS included those with physical or mental handicaps, some of them in wheelchairs or on crutches, some of them residents of institutions for for only days, others for most of their lives.

These were their friends:

Volunteers, firemen, ex-patients, doctors, psychologists, attendants, therapists, technicians, custodians, kitchen workers, secretaries, ministers and priests, including the Most Rev. Louis E. Gelineau, Catholic bishop of Providence.

This is what they did:

Munched popcorn, relaxed on the grass, danced to a Dixie beat, posed for photographs, swapped stories, listened to a few speecehs, admired Field Day's King and Queen, tossed rings at a game booth, let staff paint their faces, had steamship round of beef and barbecued chicken for dinner.

And this is what a few of them said:

"It sure is a beautiful day." - a patient at the General Hospital who, suffering from muscular dystrophy, is confined to a motorized wheelchair.

"I've been here 20 years. This is all right." - a resident of MHRH's special program for people who are both retarded and mentally ill.

"Beautiful. Best day ever." - a short-term IMH patient who has been to the hospital on several occasions.

"Next year, I hope they have more booths." - a patient at the IMH for many years.

So it was a carnival.

And, like any carnival, it brought smiles to faces and sprinkled laughter throughout conversations.

There are those that complain that Field Day is an anachronism - a gaudy display more suited to 19th-Century notions of treating patients - and perhaps there is merit to their argument. But most patients yesterday wouldn't have agreed. Neither would Thomas D. Romeo, MHRH director, or many on his staff.

Said Romeo: "The rationale for doing this is having patients and employees enjoy a day outside the environment of hospitals in an atmosphere of mutual appreciation. This is nice."

*****

Field Day still a treat at hospital and IMH

G. WAYNE MILLER

Publication Date: June 20, 1986 Page: A-20 Section: NEWS Edition: ALL

No one really knows how long it's been around, this tradition known as Field Day, only that it happens every year - even as the participants continue to dwindle, and what was once a pageant involving thousands now involves only hundreds.

Yesterday, another Field Day was staged for patients at the state-run General Hospital and the Institute of Mental Health, located on the grounds of the Howard complex.

And while the 1986 edition was a scaled-down version of earlier Field Days, it nonetheless had a lot of what every Field Day has had.

It had a parade - a long, homespun parade that followed a route past hospital buildings, offices and one unit of the Adult Correctional Institutions. It had clowns. A couple of fire engines. Games. Prizes. Free Coke and popcorn. Music.

And it had food. Not the steamship round of beef that other celebrations have featured, but hot dogs and hamburgs and salad and soda and chips, and ice cream for dessert.

Naturally, a few bureaucrats spoke.

"Governor DiPrete sends his best to everyone," said Danna Mauch, head of mental health services for the Department of Mental Health, Retardation and Hospitals, which runs both the IMH and General Hospital. "I want everyone to have a good time."

Added Peter Megrdichian, administrator of General Hospital: "I just wanted to wish those here today a good time."

Still a great day

For the patients and staff who turned out, there was enough left of a very old tradition to still bring smiles to faces.

Having fun? one patient was asked. "I'm trying," she answered. "I'm bearing up."

Once, 20 and 30 and 40 years ago, nearly 5,000 patients lived at Howard. The Field Day parade packed them six and seven deep. For many, it was the only chance to get off the ward.

Today, the combined population of the IMH and General Hospital is about 700, and those patients who are able spend a good deal of their time in the community.

But that doesn't mean Field Day yesterday wasn't special.

"A wonderful day," one patient for more than 40 years offered - smiling, of course. "Just a wonderful day.

*****

Sun shines on hospital residents

G. WAYNE MILLER

Publication Date: May 25, 1990 Page: A-03 Section: NEWS Edition: ALL

Blessed by the return of the May sun, and seemingly oblivious of a strong breeze, hundreds were at the state General Hospital yesterday to join in the festivities of Field Day, a tradition at the Howard state institutional complex since time forgotten.

"It's a chance to get some of the patients outside," said James Benedict, the hospital administrator.

"An opportunity to celebrate," said Robert L. Carl Jr., who runs retardation programs for the Department of Mental Health, Retardation and Hospitals.

"I like the sun," said the hospital's most famous resident, Hope Lincoln, 100. Hope, covered with an afghan, was one of an estimated 150 patients who - bundled in sweaters and jackets and wearing the traditional Field Day straw hat - walked outside or were brought there in wheelchairs.

For a moment, at least, patients, staff and administrators were able to put aside some of the controversy that accompanied ward closings this year.

"Getting out - it does boost your spirits," said Connie Prior, a patient who led the unsuccessful fight to prevent the closings.

There were clowns.

"It's nice to see a smile. They've got enough problems, these people," said Gene Little of Coventry, a member of the Masons' Tall Cedar Clowns.

There were cheerleaders, a marching band and a song-and-dance troupe, all from Cranston's Western Hills Junior High School.

"I think it's great because we, like, make them happy," said eighth-grader Barbara McFadden, a singer.

There was Del's lemonade. There were hamburgers, ice cream and soda. Radio station WICE was broadcasting live.

There were old friends of MHRH.

"When they get all the patients out of the buildings - that's good," said Cheryl Morin, who has been in various programs and lives on her own now.

There was a new resident of General Hospital.

"It feels funny. I love it," said Angela Petice, a respirator-dependent patient who has not been outside in four years. A patient at Rhode Island Hospital for four years, she came to Howard this week when MHRH relaxed its admission freeze to allow two new patients on General Hospital's respiratory ward.

There were four floats. The Snoopy float took the $100 first-place prize.

"Please think before you drink]" proclaimed the float put together by the staff of Benjamin Rush, the state's detoxification center. That entry featured a coffin on the back of a pickup truck.

Only a few residents from the Institute of Mental Health were on hand this year, in part because administrators have decided that patients carrying balloons and mingling with clowns sends the wrong message about mental illness. At one time, when the IMH had some 3,500 residents - more than 17 times the number it has today - Field Day was the highlight of spring and summer.

*****

At rest at last - Uprooted remains of forgotten souls finally get a proper burial

Barbara Polichetti

Publication Date: April 16, 2009 Page: B-01 Section: News Edition: All

Nameless no longer.

Under the watchful eyes of archaeologists, state Department of Transportation crews this week worked at an old state cemetery on the Cranston-Warwick line, carefully placing more than 60 granite stones that will mark the graves of the forgotten souls whose remains washed out from beneath nearby Route 37 nearly two years ago.

Since the first bones were discovered on the fringe of the former Davol Building parking lot on Sockanosset Cross Road after unusually heavy rains in June 2006, DOT archaeologist Michael Hebert has worked diligently with consultants to piece together the story of the forgotten graves and try to find as much information as possible about each individual.

The skeletal remains, some still in the shredded remnants of plain wooden coffins, were determined to be those of the sick, poor and often forgotten people who lived and died at the former State Farm, on Pontiac Avenue, around the turn of the 20th century.

As the DOT examined the erosion area near the base of the southern embankment of Route 37, it was determined that additional graves would have to be emptied to protect remains from being disturbed in the future.

Because of brass coffin plates that were often still intact, officials were able to identify the remains in 60 of the graves, but a few remained a mystery.

Perhaps most disturbing, Hebert has said, is the fact that the unearthing of the remains led to the discovery that they were only a small part of a large, forgotten potter’s field that served as a final resting place for State Farm residents from about 1873 to 1918.

He estimated that more than 3,000 graves will have to remain beneath Route 37, which was built squarely atop the graveyard.

Both the DOT and the Cranston City Council - which has jurisdiction over cemeteries within its borders - made it clear early on during the project that the people whose remains were disturbed would be treated with the respect they were apparently not accorded after their burial.

"This has been the most thought-provoking and emotional project in my 30-year career," Hebert said Wednesday. He helped pick the speckled Vermont granite for the markers and worked with the stone carvers for Scioto & Sons to include as much information as possible about each individual.

When they were first buried, their graves were marked only with plain wooden crosses that rotted away, Hebert said. Now they are identified by name, birth date, death date, assignment at the State Farm and more. Hebert and Public Archaeology Laboratory, in Pawtucket, spent months combing through census records, admission ledgers from the State Farm and other documents to determine what relatives the state wards had.

On the granite markers, they are now sons and daughters, husbands and wives. Some of the stones are heartbreaking, Hebert said, pointing out that there are a couple of infants, never named, who died at birth in the state infirmary. There was also a couple, John and Mary Shepard, who died at the almshouse within months of each other.

After the remains and coffin shards were exhumed they were stored at PAL, where every item was photographed and studied. Hebert and the PAL staff said the meager personal possessions found - glass buttons, a hair comb and only a couple of wedding rings - spoke to the bleak existence of the people who found themselves remanded to the State Farm with its poor house, work house, prison and insane asylum.

The remains were kept at PAL for more than two years while the state searched for descendants and a proper place of reburial. The remains were reinterred last summer at an old state cemetery where Pontiac Avenue in Cranston becomes Knight Street in Warwick.

On Wednesday, PAL archaeologist Jay Waller turned his collar up against a cold April wind and carefully eyed the engraved granite markers being placed flush in the earth.

"Now there’s a sense of closure –– this is what is right," he said.

"In researching this, you can’t help but get attached to some of the personal stories you discover," Waller said. "Now their graves will be marked forever and they are finally getting what they deserve."

A week at the old Institute of Mental Health, a now-closed state asylum

From the archives...

Inside the I.M.H.

G. Wayne Miller

Publication Date: November 10, 1985 Page: M-06 Section: MAGAZINE Edition: ALL

Rhode Island officials today are proud of the Institute of Mental Health, which not very long ago was considered a public disgrace. Since it was opened, 115 years ago this month, officials say, no reporter has ever been allowed to live inside the IMH with the purpose of publishing what he saw. In September, after being assured that the confidentiality of patients would be protected, IMH administrators agreed to let Journal-Bulletin reporter G. Wayne Miller spend four days and three nights on AM-9, a locked ward. Both patients and staff were told in advance who he was, and what he would be doing.

This is his report.

Part one of two parts.

TUESDAY, 10:10 A.M.

I've just been introduced to Roger, 35, who has nothing at all to say to me. Roger is unshaven. His eyes are bloodshot. His hair is dirty and short, like a British hoodlum's.

Roger is not a happy man. His mental illness, known as a bipolar disorder, has flared again, making him angry and tense. Earlier in the week, he got roaring drunk and threatened to beat up his elderly parents; the police brought him in handcuffs to the IMH. He wants out. "Roger's the name, escape's the game," he keeps repeating.

At the moment, Roger is sitting across from me in the conference room of Ward AM-9. In terms of the quality of its treatment and the caliber of its staff, AM-9 is considered among the institution's most progressive wards. The challenge on AM-9 is to take very sick people, quickly make them better and then discharge them as soon as possible.

Roger sits at the conference table, a sly grin on his face. With him are a psychiatrist, a psychologist, a social worker, an attendant, a nurse. Their job during this meeting is to pump Roger for information so that they can begin shaping a treatment plan. One of his problems is he won't take medication to control his disorder. Dr. Aimee Schwartz, the psychiatrist, is hoping that Roger will agree to try a new prescription.

During the interview, Roger skips back and forth between subjects. He lives in a tough neighborhood, he says. Takes drugs sometimes. Fights. Has a habit of abusing his body. "I almost got murdered. I have a brain concussion right now. I got a bad heart, a busted-up ear, scraped knuckles."

According to the report Dr. Schwartz has, Roger got into an argument with his parents over a pack of cigarettes. What the issue was, exactly, is unclear. The report also says he may have been hearing voices.

"Lies]" Roger says. "I'm here under false pretenses. I got kidnapped. Shanghaied."

"Why would they lie, Roger?" Dr. Schwartz asks.

"I guess they say I'm crazy."

"Are you?"

"I knock on wood I ain't."

10:30 A.M.

Roger's review is over, and now activity has shifted to the day room, where staff and patients congregate during their free moments.

Ann, a chronically depressed woman in her 50s, sits in a chair, her head buried in her hands. A chaplain comforts her. Rose, also depressed, also middle-aged, sits alone, staring blankly. For days, the staff has been unable to coax so much as a single word out of her. Other patients are more upbeat this morning. Craig, 42, is talking with a psychologist about his progress, which has been substantial. Jean, 20, is on the pay phone to her parents.

Without fully realizing it, I keep looking over my shoulder to see if anyone has crept up behind me.

And it's not just my very real fear of Roger, who strikes me as a 170-pound pressure cooker with the lid about to blow off.

No, it's the history of the IMH, known to a century of Rhode Islanders simply as Howard, after the Cranston farm that was here before. It's the weight of all those stories people tell about what goes on inside here, or what they think goes on. Stories about assembly lines for horrifying electric-shock treatments. About the poor souls subjected to the tortures of lobotomies and cold-water therapies. About the notorious back wards, where people were treated, and consequently acted, like caged animals. In short, about the state's very own "loony bin," a complex of brooding Victorian buildings where entire lifetimes were swallowed by darkness.

Since November, 1870, when it opened as the State Asylum for the Incurable Insane, the IMH has been the state's public psychiatric hospital - the temporary or permanent home for generations of mentally ill Rhode Islanders. In the last two decades, the state has moved hundreds of patients into group homes and community residences. Hundreds of others, who once would have been locked away, are now treated in the community. Today, only the sickest mentally ill go to the IMH, almost always when they are in a state of crisis. Most spend only a few days inside the hospital.

For the last two or three years, state officials have been singing the praises of the IMH: how the back wards have all been closed, how the institution has emerged from the Dark Ages to become a humane, compassionate place, where people get better - not abused.

I'm here to see.

10:45 A.M.

I'm still sitting in the day room.

Roger, who disappeared for several minutes, makes his reappearance dressed in a bathrobe. He is clean, having showered with Kwell, an antiparasitic chemical that kills body lice. He is unwilling to take his new medication. Under Rhode Island law, it would take a court order to force him; there is, as yet, no such order. He paces the hall, continuing to froth about being "shanghaied."

I wonder if Roger will approach me. He doesn't.

AM-9, located in the Adolf Meyer Building, is what is known as an admissions ward. It is affiliated with community mental-health centers in Warwick and Barrington. Under this arrangement, patients admitted to the IMH from the East Bay and West Bay areas come directly to AM-9, are treated here and eventually are discharged from here. In this way, community and hospital can stay in close touch, the idea being that patient care improves when continuity is ensured.

It is not a dreary place, this ward; neither is it especially cheerful. Because the doors are always locked, because the windows are covered with knifeproof safety screens, because there is a seclusion room at one end and restraint devices in a nearby closet - because needles and tranquilizers appear during emergencies, and pills are handed out every few hours - it is hard ever to forget just what this is: a ward in the state psychiatric hospital.

Ward AM-9 is essentially one long corridor with rooms off it. The day room, about three-quarters of the way down the corridor, predominates. It is about the size of a classroom, with seven large windows facing New London Avenue. The walls are blue. Hanging on them are bulletin boards and some Woolworth's art: framed reproductions of a ship, flowers, a duck. Thirty-five wood-frame upholstered chairs are here, along with two coffee tables, two end tables, a color TV and two card tables with inlaid chess- and checkerboards. All of the furniture is new. The chairs are comfortable. The TV gets good reception.

Off the day room is the nurses' station, a glass-enclosed booth where records and medications are kept. At the southern end of the ward are two women's bedrooms, an examination room and a seclusion room, where the most agitated patients are sequestered. The seclusion room has one bed, one window, an outside lock and no inside doorknob; inside doorknobs were removed from all IMH seclusion rooms last year after a patient, using his belt as a noose, hanged himself from one. A long corridor stretches north from the day room. Off the corridor are men's bedrooms, shower rooms, bathrooms, a kitchen. All of the bedrooms sleep two people, except one that sleeps four.

11:10 A.M.

In the day room, a couple of patients are exercising, stretching their arms, bending over to touch their toes. Mild, all of it.

Roger finally drinks a dose of lithium, his new medication. It has no immediate effect, nor will it; it can be days, even weeks, before some drugs take hold. Despite his abrasive personality, I'm beginning to feel a touch of compassion for Roger, a man whose lot in life clearly overwhelms him. Because of his illness, he has been unable to hold a steady job. He has few, if any, friends. Here on AM-9, when he thinks no one is watching, his posturing and combativeness subside and Roger sits forlornly alone, like a grammar-school kid who doesn't have anyone to play with.

NOON

Down three flights from AM-9 in a basement activity room, most of the ward's patients have gathered to prepare lunch, under the guidance of Noreen Altham, an activities coordinator. Numerous activities and therapy sessions are available weekdays: music, dance, drama, group discussions. Along with counseling and medication, these sessions help with recovery.

Ann has her good days, but today is not one of them. She sits in a chair sobbing, saying, "I'm sick to my stomach. I can't do it." In the kitchen, the remaining patients set about preparing the food. On today's menu: BLT sandwiches, fruit salad and Hawaiian Fluff, a pineapple-and-whipped-cream dessert that is Noreen's creation. There is a lot of joking and laughing as the patients become absorbed in their work.

"The idea is to give them a chance to mingle, make some decisions," Noreen says, "see if they're able to follow through on tasks, relate to one another, take directions. Most people on admissions wards hold back. They're fearful. The most important thing for them is a trustful environment."

2:55 P.M.

After a group therapy session during which we discussed our feelings (What makes us happy? Sad? What scares us?), we have returned to the day room.

The door opens and a man is brought in by two policemen. Lloyd is tall, blond, in his 20s. He wears a headband and a T-shirt. Like Roger, he has threatened his parents. He has also been smoking marijuana, a substance that doesn't mix well with his medication. Once again, I feel like all hell is about to break loose. The second that door opened, the tension level on the ward went through the ceiling.

The police unlock Lloyd's handcuffs and he is free. He marches up and down the corridor, vowing over and over in explicit terms that "I'm walkin'. I want you to know that."

3:15 P.M.

When it's time to join the staff in the conference room for his preliminary interview, Lloyd goes peacefully, albeit reluctantly.

4:10 P.M.

One of the reasons Lloyd was so agitated today, the doctors assume, is that he has refused to take his biweekly shot of Prolixin, a psychotropic drug that helps control what has been diagnosed as paranoid schizophrenia. This is common among mentally ill people in the 18-to-35 age group: Not believing they are mentally ill, they refuse treatment. After talking to the psychiatrist, Lloyd agrees to let a nurse give him his shot.

4:25 P.M.

Lloyd stands alone near the nurses' station. He is crying.

"I'm scared," he says. "I'll do anything if I can go home."

4:45 P.M.

Dinner.

I've yet to be here a full day and already meals have assumed larger-than-life proportions. For the last half-hour, I've been wondering when we will eat, what the food will be, how much I'll get. I think this is my response to boredom. Since before 4 p.m., I've done nothing but sit and watch TV while some patients napped.

Roger and Lloyd are considered elopement risks, which means their meals will be brought to them on the ward. The rest of us queue up at the door, then are led through an outside hall into a cafeteria, where we eat with another ward, AM-12. Dinner is canned peas, mashed potatoes, rolls and spinach-stuffed chicken, with chocolate pudding for dessert. The chicken and potatoes are good. I don't much like the plastic utensils.

In 10 minutes, dinner is over.

7 P.M.

After dinner, most patients' time is their own. Some watch TV, play cards, read, smoke. Some are in bed by 9 o'clock. Those with the appropriate privileges may take a walk outside or visit another building.

Movement of everyone at the IMH is controlled by a 10-stage "status" system. Those on Status One, the most permissive stage, have off-grounds privileges and are more or less free to come and go as they please, so long as they report for meals, medication and sleeping. Those on Status Ten, the least permissive, are confined to a seclusion room. Status Nine (strait-jacket or four-point restraint, when a person's legs as well as arms are tied) is used only in emergencies.

Craig is on Status Two, which means he can freely roam the grounds. And so he invites me to join him on a visit to an unlocked ward, Barry Hall 1, where longer-term patients live. Craig has several friends at Barry Hall; we meet them at a table in the Barry day room.

"You know why we're here?" says Pat, an attractive 31-year-old woman who has become one of Craig's good friends.

"No."

"Because we're insane. You want to hear something funny? See this plastic flower here? This summer, a bee was buzzing on it and then it crawled right inside. Isn't that funny?"

I laugh. The way she tells it, it is funny.

"They won't let me go because I talk to God," says Pat's friend Evelyn, a schizophrenic who looks to be in her 40s. "Out loud. Not introvertedly, extrovertedly. I accused the IMH of being the Antichrist. You know, the devil is the ruler of the world. Satan was thrown down to the earth to cause all the trouble he can. See, God hasn't reigned yet. If God had reigned, there'd be no guns, sickness, sorrow, wars, atomic weapons - nothing but happiness and joy.

"Utopia will come. It's coming. It's soon. You can tell it's going to happen because everything is in turmoil. It's all Biblical. I find peace, I find serenity in the IMH. I dine out every morning, noon and evening. I don't have that much pressure on me. Money is the root of all evil. Money causes greed, theft, murder, many sins. God is a mighty angel watching over everyone. You'll find most people here won't talk about it, but they're with Christ."

After Evelyn is through, Pat offers to buy coffee, provided Craig and I fetch it. We walk across the grounds to the main lobby of General Hospital, where we buy four coffees from a vending machine. When we return to the Barry day room, my seat at the table has been taken. Looking around the room, I see a dozen or so empty chairs. I walk over to one and begin dragging it across the floor to our table.

"Where you going with that chair?" The voice is loud, surly. I look up. A middle-aged male attendant is running toward me.

"I'm just taking it - "

"You ain't taking it nowhere. We have our rules here. You put that back."

"I'll put it back when I'm done," I explain. "I just want - "

"You put that back]" He's reached me now. For a second, I'm afraid he will hit me. It occurs to me: He thinks I am a patient from another ward.

Usually I have a slow fuse, but not tonight. I'm getting as angry as he is. There may or may not be a rule about the placement of chairs, but that's not the point. The point is that this attendant is treating me like dirt. Around and around we go, nearly coming to blows.

"Who do you think you are, anyway?" he rages.

I tell him that I am a reporter. This has an immediate calming effect on him. We agree that I may, after all, bring a chair to the table. Only not that chair. I get another one and finally sit down with the patients. Pat and Evelyn congratulate me. I've done something they've always wanted to do: stand up to this attendant, whom they describe as a bully.

As Craig and I leave, I look across the day room. There's the attendant, watching TV from the disputed chair. His chair.

Part two of two parts.

WEDNESDAY, 12:10 A.M.

Everyone has gone to sleep but me.

I'm watching Johnny Carson when the door opens and two policemen come in with Claire, an unclean, combative, obscene-tongued woman. Only 42, Claire is undergoing her 29th admission to the IMH. Her primary diagnosis: character disorder.

Claire is here because she set her hair on fire, tried to slit her wrists, was eating cigarette butts and soap, was vowing to kill her sister.

"I'm going to get a butcher knife and run it right through my sister]" she screams, fishing through an ashtray for a fresh butt. "My parents, too. Some f------ family. You know what it's like to be depressed? Huh? Day in and day out since I've been 28? Where's it going to end?"

Although her behavior is extreme, Claire's predicament is typical of the people who come to the IMH. They tend to be the sickest of the sick, in a state of crisis, frightened and confused about what is happening to them - people who are at their lowest. They tend also to be people without the financial resources or insurance to afford a bed (at $300 to $400 or more a day) in a private psychiatric hospital.

When there's no place left to go, you go to the IMH.

12:30 A.M.

Third shift has arrived, Claire has calmed down a bit and I go to bed, alone in my room. Everyone else has been asleep for three or four hours.

6:30 A.M.

Wake-up call.

I did not expect to sleep well, but I did. I had been afraid that the ward would be noisy, but it wasn't.

7 A.M.

Attendant Bernie Tramonti, Ann and I are being driven in a state car to St. Joseph Hospital, in North Providence, where a consulting physician conducts electric-shock treatments for IMH patients.

The IMH's electric-shock room was closed years ago. These days, the treatment is rare: a total of only 27 patients have had it in the last seven years, according to the Department of Mental Health, Retardation and Hospitals, which runs the IMH.

Still, electric shock is among the most common frightening images associated with mental illness - only the mention of lobotomies, no longer practiced in Rhode Island, brings the same chills to the spine. And so I am expecting a scene straight out of One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, the 1970s film about life in an insane asylum. At one point in that Oscar-winning movie, a patient screams in absolute terror and pain as he is tied down and zapped.

But it's nothing like that today, I am told. And for some deeply depressed people, it can work, when nothing else will. Exactly how the administration of voltage to the brain lifts depression is another question, as yet unanswered.

Ann's latest bout with her illness is particularly troubling to the AM-9 staff, most of whom are fond of her and remember her from years ago, when she spent more than a decade on the IMH's infamous back wards. What is so tragic, they say, is that Ann had been discharged and was doing fine living on her own for the last year or so. But late in the summer her world began to fall apart again. No one can say exactly what went wrong - just as no one can say exactly what will make her well again.

Nothing is more frustrating than this to the professionals, nothing more maddening to families and friends: the unknowns, the uncertainties of major mental illness. The mind can move a Renoir to great art, an Einstein to great thinking . . . and an Ann to a lifetime of pain.

8:05 A.M.

Ann is lying on a stretcher behind a curtain in a recovery room. A nurse has checked her vital signs and started running an IV into her arm. When the doctor is ready, the anesthesiologist injects anesthesia into the IV line. He follows that with a shot of muscle relaxant to minimize convulsion. In a few seconds, Ann is out.

The doctor rubs conducting jelly on both her temples, then straps a rubber headband around her forehead. On the inside of the band are flat metal electrodes, connected by wire to the generator, a black-and-silver machine the size of a Geiger counter. The dial has been set at 150 volts. The doctor is ready. He pushes a button. There is no sound, but Ann's body immediately tenses. Her facial muscles tighten, as if she were about to cry, and a very mild seizure rocks her body for about five seconds. Then it's over. In another 10 minutes, Ann is awake. She has no memory of the treatment, feels no pain.

10:35 A.M.

We are back on AM-9.

After spending a calm night, Lloyd is much more congenial. So is Roger. At the staff meeting, Dr. Schwartz agrees to discharge Roger to a so-called respite bed, a room in someone's home that the community mental-health center rents for transition back to the community. His condition will be followed closely by the center, which will also provide medication, counseling and other help.

During the meeting it is also decided that Claire isn't going to get better quickly, and so she will be transferred to a long-term ward. And Rose has been catatonic for so long, Dr. Schwartz orders her off all medication - a move that occasionally, inexplicably, leads to improvement.

Dr. Schwartz decides to increase Lloyd's Prolixin. He agrees. Then he demands to go home, today. The doctor says no; she wants time to see if the new dosage works. Lloyd has no choice but to stay. Under state law, people sent to the IMH may be kept up to 10 days against their will if they are judged by an IMH psychiatrist to be dangerous to themselves or others. If longer treatment is considered necessary and a patient refuses to stay, a court can order the person kept.

Dr. Schwartz wears two hats: staff psychiatrist at the IMH and medical director of the Kent County Mental Health Center, in Warwick. Her philosophy is that most patients most of the time do better in the community - provided they take their medication. Often she has been able to get judges to order mentally ill people to take medication outside the IMH. When they slip up, as Lloyd did, they can be returned to the IMH, quickly stabilized and then returned home.

NOON

Thirty years ago, when the population of the IMH was more than 3,500, patients rarely, if ever, left the hospital grounds. In the old days, the IMH was a self-contained "city," with its own post office, farm, cannery, dairy, power plant. Patients spent entire lifetimes there, without ever seeing the rest of the world. When they died, many were buried in a potter's field.

Over the past three decades, as the state has moved more and more people back to the community - a process known as deinstitutionalization - the population of the IMH has dropped to fewer than 330. Buildings have been closed or torn down. And most of the remaining patients get off the premises several times a week, to attend dance programs, shop, bowl, visit a park or a baseball game, dine out. Getting out on a regular basis prevents, or at least slows, the numbing effects of living inside an institution.

Today, several AM-9 patients get into a state van with Noreen and ride to Burger King in Apponaug for lunch. Because they have been so withdrawn, Rose and Ann stay behind, as do Roger, who is going home, and Lloyd, who is still considered an escape risk. Each patient has $3.50 to spend. Everyone gets burgers and fries. After lunch, we drive to Goddard State Park, in Warwick, where we take a short walk on the cold beach.

By now, I am comfortable with the AM-9 crew. When she's in an up mood - more and more of the time recently - Jean is a funny, easygoing young woman. So is Leslie. Craig is something of a father figure to other patients on the ward, going out of his way to console them, buy them cigarettes, reassure them they're going to be all right.

1:15 P.M.

Back on AM-9, we find that Roger has been discharged.

Since her shock treatment, Ann has perked up considerably. She is talking with the staff, enjoying a cigarette - even smiling occasionally. Lloyd is watching TV. Jean and Craig sit in a corner and chat.

Rose continues staring into space. Several staff members approach her, ask her how she's feeling. Then her husband calls. Would she like to come to the phone? For just a moment? The response is silence. Please? Your husband would like so very much to say hello. Again, silence. I have never seen such behavior in a person who wasn't deaf or autistic, and Rose is neither. Until the latest episode of her illness, in fact, she was outgoing and pleasant. But since being admitted, a month ago, about the only times she has spoken have been to suddenly, spontaneously jump up and scream, "I'm sorry for what I've done]" or "Oh, my God]" What she means, no one knows.

3:10 P.M.

Together with Craig, who will move to a group home soon, I set off for the IMH canteen, where patients with grounds privileges gather to talk, smoke, have 30-cent sodas. If any part of the IMH fits the outsider's preconception of life in an asylum, the canteen, located in the basement of a building several hundred yards from Adolf Meyer, is it.

It is a dim, cavernous room, full of smoke and noise. About two dozen patients are here. Some are playing cards. Some are talking to themselves. A couple are catnapping. One woman is wearing a Walkman radio and dancing with herself - not some old-fashioned waltz, but an honest-to-gosh, get-down boogie. One gap-toothed man wears a black witch's hat.

Immediately, I get hit up for change and cigarettes. "Got a quarter?" "Cigarette?" "Match?" "Buy me a coffee?" Few, if any, long-term patients have their own money. The government provides a small allowance every month, but this usually goes quickly. Then it's time to beg. Those rare patients who have outside sources of cash are popular.

But whatever else it may seem, the canteen provides a break from life on the wards, much as a neighborhood bar or health club provides noninstitutionalized people their chance to get away.

4:55 P.M.

At dinner, Ann is extremely talkative. I listen, fascinated.

She tells me about the food - how, considering budgetary constraints, it isn't all that bad. I agree. I can see now why the staff likes Ann so much; when she's out of the doldrums, she is a kind, intelligent, even charming woman. I feel terribly sorry for her. I feel something else, too: anger at a disorder than can be so cruel, so mysterious, so stubborn as mental illness.

7:20 P.M.

Craig and I wander down to AM-4, an old ward that has been turned into a social club run by the Providence YMCA.

Patients with the appropriate privileges come here every night for arts and crafts, board games, card games; to listen to the stereo, to chat. Special dinners and dances are also held here. AM-4 is the cheeriest place at the IMH that I have seen: soft-blue walls, curtained windows, real hanging plants, tables with tablecloths, comfortable chairs, paintings by patients, a selection of current magazines.

I take a seat and scribble a few notes. As I write, a middle-aged woman approaches, looks skeptically, then asks, "What you doing?"

"Taking notes," I say.

"To who?"

"To me."

"You write notes to yourself? You mean you don't have anybody to write notes to?"

The woman leaves, and is soon replaced by a young man who asks me, "Elvis, you got change for a one?"

"No," I say. He walks off.

The woman returns. I tell her that I am a reporter. "Maybe you're half nuts, too," she says. "Maybe you're wacky. I don't trust any of you, you know. What's your name, anyway?"

"Wayne Miller."

"Irish, huh?"

"No, English."

"I have no heart for the English," she says, disgusted.

THURSDAY, 7:05 A.M.

Breakfast is two stale doughnuts, dry cereal, juice, decaffeinated coffee. Dinner may be OK at the IMH, but breakfast is horrible. Even though I'm hungry, I only nibble at the doughnuts.

8:30 A.M.

Like a pendulum, Ann's mood has swung back to depression - a darker, uglier depression than I've ever seen in anyone. One minute she's sitting in a chair in the day room, her head bowed, sobbing; the next, she's on her feet. She runs to a wall and bangs her head against it - not some gentle tapping, but a vicious slamming that makes me cringe.

"I don't understand," Ann screams in a voice that chills me. "I don't understand. What have I done? God, what have I done?"

Psychologist Alan Feinstein and Thelma Gileau, an attendant, gently peel her off the wall and, their arms around her, try to console her. Like most of the staff I have observed on AM-9, Feinstein and Gileau are compassionate and competent. Solace in this case, however, is not enough. Ann does not calm down until a nurse leads her into her bedroom and gives her a shot of Atavan, a sedative.

8:45 A.M.

The daily ward meeting is a chance for patients to discuss their gripes. It also serves as a form of group therapy. After rearranging the day-room chairs, the staff and patients sit in a circle and introduce themselves. Surprisingly, Rose gives her name this morning; for her, this is progress.

Jean continues to be upset by her relationship with her parents: one day, their visit is welcome; the next time, they leave her in tears. The AM-9 staff would like that relationship to be a little less rocky before her planned discharge to a group home, early next week.

"What is it that makes you that way?" Mrs. Gileau asks.

"Death," says Jean, who experiences severe spells of paranoia and depression. "I don't want to die in an insane asylum."

"We're concerned about that," Mrs. Gileau says.

"Are you afraid you'll be killed at night?" asks Dr. Schwartz.

"Yes."

"Do you know how it's going to be done?" Dr. Schwartz continues.

"No. I have no idea."

"I wish I'd die," Ann bursts out. "The mental torture I'm being put through . . ."

10 A.M.

Downstairs in the activity room, some of the AM-9 patients have joined a drama class. Play acting helps the patients discuss their problems.

Jerry, a self-proclaimed minister, seizes the opportunity to preach. "Believe in miracles," he urges the group. "Trust the Lord for your salvation] Ask God to forgive you your sins] Believe He has accepted you]"

"I just want to be able to wake up one morning and feel good," says a patient from another ward. "Just be able to work one hour and feel good."

1 P.M.

We are joining patients from two long-term wards for the weekly charter-bus trip to Legion Bowladrome, in Cranston.

The Bowladrome's regular patrons stare as we file in, get our shoes and begin bowling. The AM-9 bunch, for the most part, know how to bowl; Jean and Lloyd are actually quite good. Some of the long-term patients, however, haven't the slightest idea of what's going on. One walks to the line, ball in hand, and drops it onto the alley; it dribbles into the gutter. Another has a decent toss, but stares vacantly at the alley when the pins drop. A third steps to the line and casually bowls a strike. I'm amazed.

For these long-term patients - many of whom lived on the back wards before they were closed - just being able to get outside the IMH is tremendous progress. Some of the ones who can bowl couldn't not too long ago.

While we are bowling, a patient wanders out of the Bowladrome, unnoticed until she is gone. On the way back to the IMH we search for her, without success. Several hours later, after she has ordered and happily eaten a dinner for which she cannot pay, the police are called. Cranston police, used to such runaways, bring her back.

EARLY EVENING

Three more patients have been admitted: a young man who threatened suicide, a 39-year-old woman who overdosed on sleeping pills, a 21-year-old woman who became paranoid that someone was trying to kill her baby. A close watch is ordered for all three.

FRIDAY, 10:30 A.M.

Lloyd's behavior has been exemplary, his new dosage seems to be working well, and so Dr. Schwartz decides to discharge him today. Russ Partridge, a social worker from the community mental-health center, gives Lloyd the word.

"Thanks] Really? Thanks]" Lloyd says excitedly. "No problems this time. I promise. I'm not going to let anyone down."

"You've got to take your meds," Russ warns.

"I will this time, I promise. They make me feel better. Before, I was blah-blah-blah. My head was twisted. Now, I feel better."

1:15 P.M.

In the day room, Ann is sitting, head in hands. Rose is staring at the walls - but her eyes are following the movements of people in the room.

Jean's privileges have been increased, and she joins Craig and me for a stroll about the grounds. If all goes well, she will get out the first part of the week. Craig, too, should get out sometime this month. Both are anxious, but eager, about their impending discharges.

I am leaving, too, in another hour or two. I depart with these thoughts from Danna Mauch, director of state Mental Health Services:

"The IMH is a place where people now come as a last resort. Ultimately, we should be judged by the extent to which we appreciate the profound pain and suffering experienced by people with mental disabilities."

G. Wayne Miller is a Journal-Bulletin staff writer.

Inside the I.M.H.

G. Wayne Miller

Publication Date: November 10, 1985 Page: M-06 Section: MAGAZINE Edition: ALL

Rhode Island officials today are proud of the Institute of Mental Health, which not very long ago was considered a public disgrace. Since it was opened, 115 years ago this month, officials say, no reporter has ever been allowed to live inside the IMH with the purpose of publishing what he saw. In September, after being assured that the confidentiality of patients would be protected, IMH administrators agreed to let Journal-Bulletin reporter G. Wayne Miller spend four days and three nights on AM-9, a locked ward. Both patients and staff were told in advance who he was, and what he would be doing.

This is his report.

Part one of two parts.

TUESDAY, 10:10 A.M.

I've just been introduced to Roger, 35, who has nothing at all to say to me. Roger is unshaven. His eyes are bloodshot. His hair is dirty and short, like a British hoodlum's.

Roger is not a happy man. His mental illness, known as a bipolar disorder, has flared again, making him angry and tense. Earlier in the week, he got roaring drunk and threatened to beat up his elderly parents; the police brought him in handcuffs to the IMH. He wants out. "Roger's the name, escape's the game," he keeps repeating.

At the moment, Roger is sitting across from me in the conference room of Ward AM-9. In terms of the quality of its treatment and the caliber of its staff, AM-9 is considered among the institution's most progressive wards. The challenge on AM-9 is to take very sick people, quickly make them better and then discharge them as soon as possible.

Roger sits at the conference table, a sly grin on his face. With him are a psychiatrist, a psychologist, a social worker, an attendant, a nurse. Their job during this meeting is to pump Roger for information so that they can begin shaping a treatment plan. One of his problems is he won't take medication to control his disorder. Dr. Aimee Schwartz, the psychiatrist, is hoping that Roger will agree to try a new prescription.

During the interview, Roger skips back and forth between subjects. He lives in a tough neighborhood, he says. Takes drugs sometimes. Fights. Has a habit of abusing his body. "I almost got murdered. I have a brain concussion right now. I got a bad heart, a busted-up ear, scraped knuckles."

According to the report Dr. Schwartz has, Roger got into an argument with his parents over a pack of cigarettes. What the issue was, exactly, is unclear. The report also says he may have been hearing voices.

"Lies]" Roger says. "I'm here under false pretenses. I got kidnapped. Shanghaied."

"Why would they lie, Roger?" Dr. Schwartz asks.

"I guess they say I'm crazy."

"Are you?"

"I knock on wood I ain't."

10:30 A.M.

Roger's review is over, and now activity has shifted to the day room, where staff and patients congregate during their free moments.

Ann, a chronically depressed woman in her 50s, sits in a chair, her head buried in her hands. A chaplain comforts her. Rose, also depressed, also middle-aged, sits alone, staring blankly. For days, the staff has been unable to coax so much as a single word out of her. Other patients are more upbeat this morning. Craig, 42, is talking with a psychologist about his progress, which has been substantial. Jean, 20, is on the pay phone to her parents.

Without fully realizing it, I keep looking over my shoulder to see if anyone has crept up behind me.

And it's not just my very real fear of Roger, who strikes me as a 170-pound pressure cooker with the lid about to blow off.

No, it's the history of the IMH, known to a century of Rhode Islanders simply as Howard, after the Cranston farm that was here before. It's the weight of all those stories people tell about what goes on inside here, or what they think goes on. Stories about assembly lines for horrifying electric-shock treatments. About the poor souls subjected to the tortures of lobotomies and cold-water therapies. About the notorious back wards, where people were treated, and consequently acted, like caged animals. In short, about the state's very own "loony bin," a complex of brooding Victorian buildings where entire lifetimes were swallowed by darkness.

Since November, 1870, when it opened as the State Asylum for the Incurable Insane, the IMH has been the state's public psychiatric hospital - the temporary or permanent home for generations of mentally ill Rhode Islanders. In the last two decades, the state has moved hundreds of patients into group homes and community residences. Hundreds of others, who once would have been locked away, are now treated in the community. Today, only the sickest mentally ill go to the IMH, almost always when they are in a state of crisis. Most spend only a few days inside the hospital.

For the last two or three years, state officials have been singing the praises of the IMH: how the back wards have all been closed, how the institution has emerged from the Dark Ages to become a humane, compassionate place, where people get better - not abused.

I'm here to see.

10:45 A.M.

I'm still sitting in the day room.

Roger, who disappeared for several minutes, makes his reappearance dressed in a bathrobe. He is clean, having showered with Kwell, an antiparasitic chemical that kills body lice. He is unwilling to take his new medication. Under Rhode Island law, it would take a court order to force him; there is, as yet, no such order. He paces the hall, continuing to froth about being "shanghaied."

I wonder if Roger will approach me. He doesn't.

AM-9, located in the Adolf Meyer Building, is what is known as an admissions ward. It is affiliated with community mental-health centers in Warwick and Barrington. Under this arrangement, patients admitted to the IMH from the East Bay and West Bay areas come directly to AM-9, are treated here and eventually are discharged from here. In this way, community and hospital can stay in close touch, the idea being that patient care improves when continuity is ensured.

It is not a dreary place, this ward; neither is it especially cheerful. Because the doors are always locked, because the windows are covered with knifeproof safety screens, because there is a seclusion room at one end and restraint devices in a nearby closet - because needles and tranquilizers appear during emergencies, and pills are handed out every few hours - it is hard ever to forget just what this is: a ward in the state psychiatric hospital.

Ward AM-9 is essentially one long corridor with rooms off it. The day room, about three-quarters of the way down the corridor, predominates. It is about the size of a classroom, with seven large windows facing New London Avenue. The walls are blue. Hanging on them are bulletin boards and some Woolworth's art: framed reproductions of a ship, flowers, a duck. Thirty-five wood-frame upholstered chairs are here, along with two coffee tables, two end tables, a color TV and two card tables with inlaid chess- and checkerboards. All of the furniture is new. The chairs are comfortable. The TV gets good reception.

Off the day room is the nurses' station, a glass-enclosed booth where records and medications are kept. At the southern end of the ward are two women's bedrooms, an examination room and a seclusion room, where the most agitated patients are sequestered. The seclusion room has one bed, one window, an outside lock and no inside doorknob; inside doorknobs were removed from all IMH seclusion rooms last year after a patient, using his belt as a noose, hanged himself from one. A long corridor stretches north from the day room. Off the corridor are men's bedrooms, shower rooms, bathrooms, a kitchen. All of the bedrooms sleep two people, except one that sleeps four.

11:10 A.M.

In the day room, a couple of patients are exercising, stretching their arms, bending over to touch their toes. Mild, all of it.

Roger finally drinks a dose of lithium, his new medication. It has no immediate effect, nor will it; it can be days, even weeks, before some drugs take hold. Despite his abrasive personality, I'm beginning to feel a touch of compassion for Roger, a man whose lot in life clearly overwhelms him. Because of his illness, he has been unable to hold a steady job. He has few, if any, friends. Here on AM-9, when he thinks no one is watching, his posturing and combativeness subside and Roger sits forlornly alone, like a grammar-school kid who doesn't have anyone to play with.

NOON

Down three flights from AM-9 in a basement activity room, most of the ward's patients have gathered to prepare lunch, under the guidance of Noreen Altham, an activities coordinator. Numerous activities and therapy sessions are available weekdays: music, dance, drama, group discussions. Along with counseling and medication, these sessions help with recovery.

Ann has her good days, but today is not one of them. She sits in a chair sobbing, saying, "I'm sick to my stomach. I can't do it." In the kitchen, the remaining patients set about preparing the food. On today's menu: BLT sandwiches, fruit salad and Hawaiian Fluff, a pineapple-and-whipped-cream dessert that is Noreen's creation. There is a lot of joking and laughing as the patients become absorbed in their work.

"The idea is to give them a chance to mingle, make some decisions," Noreen says, "see if they're able to follow through on tasks, relate to one another, take directions. Most people on admissions wards hold back. They're fearful. The most important thing for them is a trustful environment."

2:55 P.M.

After a group therapy session during which we discussed our feelings (What makes us happy? Sad? What scares us?), we have returned to the day room.

The door opens and a man is brought in by two policemen. Lloyd is tall, blond, in his 20s. He wears a headband and a T-shirt. Like Roger, he has threatened his parents. He has also been smoking marijuana, a substance that doesn't mix well with his medication. Once again, I feel like all hell is about to break loose. The second that door opened, the tension level on the ward went through the ceiling.

The police unlock Lloyd's handcuffs and he is free. He marches up and down the corridor, vowing over and over in explicit terms that "I'm walkin'. I want you to know that."

3:15 P.M.

When it's time to join the staff in the conference room for his preliminary interview, Lloyd goes peacefully, albeit reluctantly.

4:10 P.M.

One of the reasons Lloyd was so agitated today, the doctors assume, is that he has refused to take his biweekly shot of Prolixin, a psychotropic drug that helps control what has been diagnosed as paranoid schizophrenia. This is common among mentally ill people in the 18-to-35 age group: Not believing they are mentally ill, they refuse treatment. After talking to the psychiatrist, Lloyd agrees to let a nurse give him his shot.

4:25 P.M.

Lloyd stands alone near the nurses' station. He is crying.

"I'm scared," he says. "I'll do anything if I can go home."

4:45 P.M.

Dinner.

I've yet to be here a full day and already meals have assumed larger-than-life proportions. For the last half-hour, I've been wondering when we will eat, what the food will be, how much I'll get. I think this is my response to boredom. Since before 4 p.m., I've done nothing but sit and watch TV while some patients napped.

Roger and Lloyd are considered elopement risks, which means their meals will be brought to them on the ward. The rest of us queue up at the door, then are led through an outside hall into a cafeteria, where we eat with another ward, AM-12. Dinner is canned peas, mashed potatoes, rolls and spinach-stuffed chicken, with chocolate pudding for dessert. The chicken and potatoes are good. I don't much like the plastic utensils.

In 10 minutes, dinner is over.

7 P.M.

After dinner, most patients' time is their own. Some watch TV, play cards, read, smoke. Some are in bed by 9 o'clock. Those with the appropriate privileges may take a walk outside or visit another building.

Movement of everyone at the IMH is controlled by a 10-stage "status" system. Those on Status One, the most permissive stage, have off-grounds privileges and are more or less free to come and go as they please, so long as they report for meals, medication and sleeping. Those on Status Ten, the least permissive, are confined to a seclusion room. Status Nine (strait-jacket or four-point restraint, when a person's legs as well as arms are tied) is used only in emergencies.

Craig is on Status Two, which means he can freely roam the grounds. And so he invites me to join him on a visit to an unlocked ward, Barry Hall 1, where longer-term patients live. Craig has several friends at Barry Hall; we meet them at a table in the Barry day room.

"You know why we're here?" says Pat, an attractive 31-year-old woman who has become one of Craig's good friends.

"No."

"Because we're insane. You want to hear something funny? See this plastic flower here? This summer, a bee was buzzing on it and then it crawled right inside. Isn't that funny?"

I laugh. The way she tells it, it is funny.

"They won't let me go because I talk to God," says Pat's friend Evelyn, a schizophrenic who looks to be in her 40s. "Out loud. Not introvertedly, extrovertedly. I accused the IMH of being the Antichrist. You know, the devil is the ruler of the world. Satan was thrown down to the earth to cause all the trouble he can. See, God hasn't reigned yet. If God had reigned, there'd be no guns, sickness, sorrow, wars, atomic weapons - nothing but happiness and joy.

"Utopia will come. It's coming. It's soon. You can tell it's going to happen because everything is in turmoil. It's all Biblical. I find peace, I find serenity in the IMH. I dine out every morning, noon and evening. I don't have that much pressure on me. Money is the root of all evil. Money causes greed, theft, murder, many sins. God is a mighty angel watching over everyone. You'll find most people here won't talk about it, but they're with Christ."

After Evelyn is through, Pat offers to buy coffee, provided Craig and I fetch it. We walk across the grounds to the main lobby of General Hospital, where we buy four coffees from a vending machine. When we return to the Barry day room, my seat at the table has been taken. Looking around the room, I see a dozen or so empty chairs. I walk over to one and begin dragging it across the floor to our table.

"Where you going with that chair?" The voice is loud, surly. I look up. A middle-aged male attendant is running toward me.

"I'm just taking it - "

"You ain't taking it nowhere. We have our rules here. You put that back."

"I'll put it back when I'm done," I explain. "I just want - "

"You put that back]" He's reached me now. For a second, I'm afraid he will hit me. It occurs to me: He thinks I am a patient from another ward.

Usually I have a slow fuse, but not tonight. I'm getting as angry as he is. There may or may not be a rule about the placement of chairs, but that's not the point. The point is that this attendant is treating me like dirt. Around and around we go, nearly coming to blows.

"Who do you think you are, anyway?" he rages.

I tell him that I am a reporter. This has an immediate calming effect on him. We agree that I may, after all, bring a chair to the table. Only not that chair. I get another one and finally sit down with the patients. Pat and Evelyn congratulate me. I've done something they've always wanted to do: stand up to this attendant, whom they describe as a bully.

As Craig and I leave, I look across the day room. There's the attendant, watching TV from the disputed chair. His chair.

Part two of two parts.

WEDNESDAY, 12:10 A.M.

Everyone has gone to sleep but me.

I'm watching Johnny Carson when the door opens and two policemen come in with Claire, an unclean, combative, obscene-tongued woman. Only 42, Claire is undergoing her 29th admission to the IMH. Her primary diagnosis: character disorder.

Claire is here because she set her hair on fire, tried to slit her wrists, was eating cigarette butts and soap, was vowing to kill her sister.

"I'm going to get a butcher knife and run it right through my sister]" she screams, fishing through an ashtray for a fresh butt. "My parents, too. Some f------ family. You know what it's like to be depressed? Huh? Day in and day out since I've been 28? Where's it going to end?"

Although her behavior is extreme, Claire's predicament is typical of the people who come to the IMH. They tend to be the sickest of the sick, in a state of crisis, frightened and confused about what is happening to them - people who are at their lowest. They tend also to be people without the financial resources or insurance to afford a bed (at $300 to $400 or more a day) in a private psychiatric hospital.

When there's no place left to go, you go to the IMH.

12:30 A.M.

Third shift has arrived, Claire has calmed down a bit and I go to bed, alone in my room. Everyone else has been asleep for three or four hours.

6:30 A.M.

Wake-up call.

I did not expect to sleep well, but I did. I had been afraid that the ward would be noisy, but it wasn't.

7 A.M.

Attendant Bernie Tramonti, Ann and I are being driven in a state car to St. Joseph Hospital, in North Providence, where a consulting physician conducts electric-shock treatments for IMH patients.

The IMH's electric-shock room was closed years ago. These days, the treatment is rare: a total of only 27 patients have had it in the last seven years, according to the Department of Mental Health, Retardation and Hospitals, which runs the IMH.

Still, electric shock is among the most common frightening images associated with mental illness - only the mention of lobotomies, no longer practiced in Rhode Island, brings the same chills to the spine. And so I am expecting a scene straight out of One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, the 1970s film about life in an insane asylum. At one point in that Oscar-winning movie, a patient screams in absolute terror and pain as he is tied down and zapped.

But it's nothing like that today, I am told. And for some deeply depressed people, it can work, when nothing else will. Exactly how the administration of voltage to the brain lifts depression is another question, as yet unanswered.

Ann's latest bout with her illness is particularly troubling to the AM-9 staff, most of whom are fond of her and remember her from years ago, when she spent more than a decade on the IMH's infamous back wards. What is so tragic, they say, is that Ann had been discharged and was doing fine living on her own for the last year or so. But late in the summer her world began to fall apart again. No one can say exactly what went wrong - just as no one can say exactly what will make her well again.

Nothing is more frustrating than this to the professionals, nothing more maddening to families and friends: the unknowns, the uncertainties of major mental illness. The mind can move a Renoir to great art, an Einstein to great thinking . . . and an Ann to a lifetime of pain.

8:05 A.M.

Ann is lying on a stretcher behind a curtain in a recovery room. A nurse has checked her vital signs and started running an IV into her arm. When the doctor is ready, the anesthesiologist injects anesthesia into the IV line. He follows that with a shot of muscle relaxant to minimize convulsion. In a few seconds, Ann is out.

The doctor rubs conducting jelly on both her temples, then straps a rubber headband around her forehead. On the inside of the band are flat metal electrodes, connected by wire to the generator, a black-and-silver machine the size of a Geiger counter. The dial has been set at 150 volts. The doctor is ready. He pushes a button. There is no sound, but Ann's body immediately tenses. Her facial muscles tighten, as if she were about to cry, and a very mild seizure rocks her body for about five seconds. Then it's over. In another 10 minutes, Ann is awake. She has no memory of the treatment, feels no pain.

10:35 A.M.

We are back on AM-9.

After spending a calm night, Lloyd is much more congenial. So is Roger. At the staff meeting, Dr. Schwartz agrees to discharge Roger to a so-called respite bed, a room in someone's home that the community mental-health center rents for transition back to the community. His condition will be followed closely by the center, which will also provide medication, counseling and other help.

During the meeting it is also decided that Claire isn't going to get better quickly, and so she will be transferred to a long-term ward. And Rose has been catatonic for so long, Dr. Schwartz orders her off all medication - a move that occasionally, inexplicably, leads to improvement.

Dr. Schwartz decides to increase Lloyd's Prolixin. He agrees. Then he demands to go home, today. The doctor says no; she wants time to see if the new dosage works. Lloyd has no choice but to stay. Under state law, people sent to the IMH may be kept up to 10 days against their will if they are judged by an IMH psychiatrist to be dangerous to themselves or others. If longer treatment is considered necessary and a patient refuses to stay, a court can order the person kept.