I have spent much of my career in journalism writing about social-justice issues, highlighting programs and people who have done good, and exposing systems that have failed those needy and vulnerable members of society they were intended to serve.

My continuing series

"Mental Health in Rhode Island" examines the current status of the treatment and care of children and adults living with mental illness -- many of them poor and lacking the means themselves to better their lives. A total system failure. Total disgrace.

This year, I turned my attention to the system that is supposed to serve intellectually and developmentally disabled people. That system was once a national model -- but, like the parallel system that serves people living with mental illness, is now in shambles.

Here is my exposé, published in The Providence Journal online on May 20, 2016, and on the front page of the Sunday Journal on May 22, 2016.

Care in crisis for R.I.'s intellectually and developmentally disabled

The way R.I. cares for people with developmental disabilities was once a model for the nation. Today it's a system in crisis.

|

| Caregivers Rachel Morgan, supervisor for a Perspectives group home, and Carrie Manne, a direct support professional, interact with group home resident Danielle DeGregorio, right, by playing the drums. Providence Journal/Bob Breidenbach |

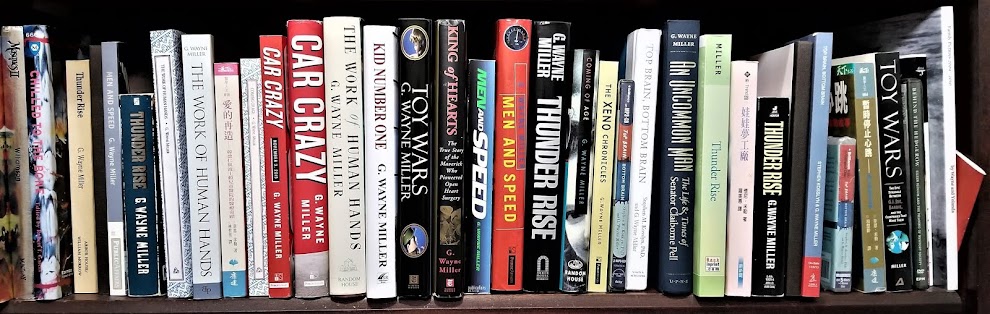

By G. Wayne Miller

Journal Staff Writer Posted May. 20, 2016 at 6:22 pmUpdated May 20, 2016 at 6:23 PM

PROVIDENCE, R.I. — Years of budget cuts and failed government leadership have diminished Rhode Island's system of care for intellectually and developmentally disabled people from a national model two decades ago into a deeply troubled system today where financial considerations, not quality of life, often are the deciding factor.

And many individuals and families largely without voice, wealth or political power – some of them among Rhode Island's most vulnerable residents – have been imperiled.

That is the conclusion of a Providence Journal investigation that began following the February death, allegedly from staff abuse, of Barbara A. Annis, 70. She was a resident of a group home run by the Department of Behavioral Healthcare, Developmental Disabilities and Hospitals (BHDDH), which funds and regulates the state's developmental disabilities system.

Among The Journal's findings:

— From 2008 through today, funding for services to the intellectually and developmentally disabled dropped from $260.2 million to $230.9 million even as the statewide numbers of those people remained roughly the same. That is an inflation-adjusted decrease of almost $60 million, as measured by the Consumer Price Index.

— A $26.1-million cut from 2011 to 2012 — a decrease of nearly 11 percent in that single year – proved particularly punishing to private agencies that rely on funding set by BHDDH. These agencies, which serve about 4,000 people, have never fully recovered.

— Pay for direct-care staff in the private sector of the BHDDH-funded system averages under $12 an hour, or less than $23,000 annually, for a full-time position. The average janitor in America earns more, according to the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics.

— As a result, hundreds of these direct-care workers — some with life-and-death responsibilities — must work second or third jobs. Many receive government assistance such as from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.

— Motivated by the humanitarian "desire to support people with special and unique needs," a majority of these private workers want to stay in the field but more than half say the low pay may give them no choice but to leave, a 2015 Community Providers Network of Rhode Island survey found.

— The state still does not comply with a 2014 federal Department of Justice consent decree in which it agreed to correct gross violations of the Americans with Disabilities Act. Last week, District Court Judge John J. McConnell Jr. threatened fines of up to $1 million a year if the state does not meet a series of more than 20 compliance benchmarks, most in the next few weeks.

— These factors have combined to place Rhode Island 39th overall of the 50 states and District of Columbia, according to United Cerebral Palsy's 2015 Case for Inclusion study, which measures quality of life. The state ranked 36th in the critical Reaching Those in Need metric.

One of the nation's leading experts on developmental disability, A. Anthony Antosh, professor of special education at Rhode Island College and director of the school's Paul V. Sherlock Center on Disabilities, summarizes the situation this way:

"We went from a decently functioning system that was community-based, that was humane, that encouraged individual choice and that was considered to be one of the best in the country to a system that is underfunded, has poorly paid staff and a significant number of staff shortages, mostly because of budget cuts over several years and a set of regulations and policies that limited options, decreased supports for many people, and made it really hard to run a quality system."

For much of the 20th century, the Ladd Center, in Exeter, was the primary provider of care to many of the state's developmentally disabled residents. Founded in 1907 as a compassionate alternative to prisons and poorhouses, Ladd degenerated into an institution where indignity, neglect and abuse were rife. At its height, more than 1,000 people were warehoused there.

In 1956, The Providence Journal began publishing investigative stories. A new Journal series started in 1977 revealed that the institution remained underfunded and understaffed, fire protection was dangerously deficient, residents’ teeth were routinely extracted without anesthetic and doctors failed to diagnose infections, diabetes and broken limbs. Several deaths had resulted.

Relatives filed a federal class-action lawsuit, advocates pressured, legislators and governors responded, and the Department of Mental Health, Retardation and Hospitals (MHRH), BHDDH's predecessor, built a model community system which statewide voters endorsed – not only philosophically, but with tens of millions of bond dollars.

On March 25, 1994, Ladd closed.

"The beast is dead," Robert L. Carl Jr., who headed MHRH's Division of Developmental Disabilities, said on that final day. "Nazi Germany killed these people. Rhode Island made a commitment to treat them with dignity and respect."

For years, the community system remained a national leader as shocking headlines receded into the past. Then, as the economy soured, "fiscal responsibility" became a mantra.

Developmental disability services received $260.2 million in 2008 for a caseload of 4,381 individuals. During the next four years, funding declined annually, dropping to $216.5 million in 2012 – a decrease of $43.7 million, or nearly 20 percent. The caseload was relatively stable.

Meanwhile, several senior developmental disabilities officials – people who carried institutional wisdom from Ladd's dark days – left BHDDH, lost to retirement or objection to what was happening. A similar scenario was unfolding in the state's once-proud community mental-health system, which today also is troubled.

And legislative champions had all but disappeared from the General Assembly. The last tireless one, Rep. Paul Sherlock, considered the father of special education in Rhode Island, died in 2004 after serving for a quarter of a century.

After that, says Antosh, whose workplace bears the late representative's name, "there essentially were no more legislative advocates, at least not with the oomph that Sherlock had."

The director of BHDDH during much of this period was Craig S. Stenning, who became director in 2008 after joining the department in 2000. Previously, he was founder and CEO of CODAC Behavioral Healthcare, which specializes in substance-abuse treatment, and a politician: Cranston School Committee chairman from 1978 to 1982, a member of the Cranston City Council from 1982 to 1992.

Lincoln D. Chafee had not yet begun his term as governor when he announced, in December 2010, that he was retaining Stenning.

"BHDDH is one of the state's most important departments, providing care and support for some of our most vulnerable citizens," Chafee said. "With our state facing fiscal uncertainty, we must seek out reduced costs and savings — but not at the expense of the services disadvantaged Rhode Islanders depend on. I feel confident that Craig can accomplish that difficult but necessary task."

|

| Stenning, left, and Chafee, center. |

On Chafee's and Stenning's watch, funding for BHDDH's Developmental Disabilities Program declined from $242.6 million in the 2011 fiscal year to $239.5 million in 2015, while the caseload dropped from 4,381 to 4,018. The 2012 year, however, told the critical story.

That's when the $26.1-million cut forced private providers to lay off staff, cut wages, reduce training and eliminate or reduce services including speech and physical therapy. In his proposed 2012 budget, Chafee had recommended a less severe cut: of $18.2 million, or 7.5 percent. But under the leadership of former Speaker Gordon Fox, now serving time in prison on federal corruption charges, the House approved the larger decrease. The BHDDH budget climbed incrementally in each of the next three years.

Stenning, now an executive with New York-based Fedcap, a social-services organization, declined a request for an interview but said he would consider questions submitted in writing. When he received seven questions by email, he declined to answer any.

Chafee, however, was willing to comment.

In an interview last week, he said that the 2012 budget year was an unusually "tough" one, and his priority was reversing certain policies adopted by his predecessor, Donald Carcieri. "Higher education and the cities and towns had just taken massive cuts.”

The Department of Justice's involvement in Rhode Island's system of care to intellectually and developmentally disabled people began in January 2013, when its Civil Rights Division initiated an investigation. A year later, the division concluded the state was in violation of the Americans with Disabilities Act — which had passed in 1990 with the enthusiastic support of the late Sen. John H. Chafee, Lincoln's father.

"Over twenty years ago," the Department wrote in a 32-page report, "Rhode Island was a national leader in shifting its state service system away from segregated residential care. The State closed its state institution for individuals with developmental disabilities, the Ladd School, ‘through strong collaboration with multiple stakeholders, including self-advocates, family members … providers, and community leaders.'"

That was then.

Citing the "the state's failure to develop a sufficient quantity of integrated transition, employment, vocational and day services and supports for individuals with I/DD," the department on Jan. 6, 2014, threatened to sue if the state did not move toward ADA compliance.

Three months later, Rhode Island signed a 36-page consent decree outlining a 10-year-plan of correction. Today, it still does not comply with the decree, and that prompted Judge McConnell to issue last week’s stern warning.

"The violation of the ADA is essentially caused by the failure of the state to provide resources," says Antosh. Had there not been this chronic "absence," he asserts, "I do not believe the Department of Justice would have ever come to the state."

Budget cuts have been especially harsh on Rhode Island's roughly 30 state-funded private providers, which serve the vast majority of the state's intellectually and developmentally disabled population.

The largest provider, North Kingstown-based Perspectives Corporation, saw revenues for its 24-hour programs decline from $14 million in 2006 to $10.5 million last year. During the period, the residential population actually rose – from 139 to 149 – while staff declined, from 439 to 326.

More staff reductions, Perspectives founder and CEO David C. Ruppell believed, would have jeopardized safety. Even though it prides itself on the quality of its staff training, Perspectives was forced to reduce it, while also eliminating or cutting back on occupational, physical and speech therapies.

|

| Perspectives group home resident Robert Rendine, right, with Ruppell. |

"You can't get rid of all your direct-care staff and all your administrators," says Ruppell. "You can't get rid of your financial people because they have to do the crazy billing. So a lot of training was cut."

And wages stagnated. Starting pay for direct-care staff at Perspectives is $11 an hour, one of the more generous rates among private providers.

"We're competing with McDonalds," Ruppell says. "That's who is helping and taking care of our most disabled people in the state."

Among them is Danielle DeGregorio, 33, who lives in a Perspectives group home in East Greenwich. Danielle has a severe developmental disability, along with anxiety and mood disorders. She has lived at the home since she was a teenager. She enjoys drumming and animals, visits with her father, and is known for her sense of humor.

Some consumers, advocates and relatives have protested the cuts, but fear of retribution has silenced others, Ruppell says. "Under the last administration, parents found if they complained too much the funding to their child was suddenly cut. They didn't have to do it very many times to scare the bejesus out of these moms and dads."

Approximately 4,000 people are employed in the private system, according to the Community Provider Network of Rhode Island; they serve about 3,800 people.

A much smaller number of employees, approximately 370, work in BHDDH's Rhode Island Community Living and Supports (RICLAS) division, which ran the group home, since closed, where Barbara Annis lived. They serve an even smaller number of people: 152, according to BHDDH.

These unionized state workers are paid more than private staff: a community living aide, for example, earns from $35,668 to $38,744 a year (not including overtime), compared with less than $23,000 annually for the a direct-care worker in the non-unionized private sector.

According to House Finance Committee data, BHDDH currently spends $51,257 per person for services provided by community-based programs. The cost per person for programs operated directly by the state – including the 152 individuals in RICLAS homes – was more than triple, $175,383 per person. The substantial medical needs of some of these people in RICLAS homes account for some of the greater costs.

Nonetheless, this disparity has been a factor in the state's improper use of the Supports Intensity Scale (SIS) assessment tool, endorsed by the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, a professional organization headquartered in Washington. Designed to determine an individual's needs, not the cost of services required to meet them, the state has used the scale to move some people to a lower-need tier only to save dollars.

In its January 2014 report, the Department of Justice chastised the state for this misuse of SIS, noting that BHDDH both administers the SIS system and determines funding: "This is a seeming conflict of interest because the need to keep consumers' resource allocations within budget may influence staff to administer the SIS in a way that reaches the pre-determined budgetary result."

Providers and many families assert that BHDHH continues to do just that by arbitrarily recategorizing. And while appeals are possible and sometimes granted, the appeal process, they say, is frustratingly complex and can take weeks or months – during which needed services may be withheld.

Governor Raimondo was in office just hours in January 2015 when she announced she would not reappoint Stenning. His successor, Maria Montanaro — former CEO of Thundermist Health Center and then CEO of Magellan Healthcare of Iowa — was similarly disturbed by what she found inside the department, even before she officially started work.

"It's a challenging environment, made all the more challenging by some of the crises that greeted me when I came in the door," Montanaro said on Feb. 26, 2015, when the Senate Health and Human Services Committee unanimously recommended her confirmation.

The reality was worse than she imagined, Montanaro says she discovered after a few weeks on the job.

"I didn't realize the state of affairs that I was inheriting in DD, which was a system that had been chronically underfunded for the better part of a decade," she said last week. "Some of those cuts were so devastating to the private-sector system that the capacity for us to actually care for individuals as we are required under the Medicaid rules was really in serious jeopardy."

Today, she says, "we have a lot of challenges in the DD department to take the existing resources that are budgeted to us and really meet the mandates of service. That has been noted by the court monitor for the DOJ consent decree as well as the judge as well as all of us within the department. And that is: we really need investments made in the DD system."

The Developmental Disabilities Program enacted budget for the fiscal year that ends June 30 was $230.9 million, a decrease of $8.6 million, or 3.5 percent, from the year before. Funding rises $4.3 million, or almost 2 percent, in the governor's proposed 2017 budget, now before the General Assembly; the increase would support a 45-cent hourly raise in the private sector. Reductions in residential programs would free almost $16.2 million for other private-provider programs.

"We have an administration now that recognizes the problems resulting from chronic reductions in funding and is taking steps to correct the current trajectory," Donna Martin, executive director of the Community Provider Network of Rhode Island, tells The Journal. "Unfortunately, it will take some time to rebound from so many years of fiscal deprivation and the lack of a clear vision for integrated, community-based services."

———

By the numbers:

$260.2 million: R.I. spending in 2008 on developmental disabilities

$230.9 million: What state will spend in fiscal 2016

$58.2 million: Inflation-adjusted decrease

$1 million: Potential annual federal fine

— gwmiller@providencejournal.com

(401) 277-7380

On Twitter: @GWayneMiller

And this ran as a sidebar:

Abused former Ladd resident loves current group home, upset by cut

By G. Wayne Miller

Journal Staff Writer Posted May. 20, 2016 @ 6:22 pm

NORTH KINGSTOWN, R.I. — Richard Rendine's alcoholic mother treated him cruelly when he was a young child.

"She smacked me, hit me. She vacuum-broomed me," he says. "That's why my godfather put me in Ladd School. Because I kind of hurt."

Along with his brother, Rendine, 66, was sent to the Ladd Center, Rhode Island's now-closed institution for intellectually and developmentally disabled people, in 1958. He stayed two decades, coming of age during a period when Ladd residents were routinely abused and neglected. Some died as a result.

Rendine was not spared.

"They were doing bad things to me down there when I was a kid," he says. "I was child-abused by my mother. And I was child-abused by them down there."

In 1978, Rendine moved from Ladd to a group home. He lives in one now, in Wakefield, operated by Perspectives Corporation.

He has a girlfriend. He enjoys hiking, walking on the beach, listening to his albums.

Favorite groups?

"The Beach Boys. The Monkees. The Four Tops. The Beatles. Elvis Presley. And Michael Jackson. And Steve Wonder. And the one who died in the last month: Prince."

Life is good. But it used to be better.

"When the budget cuts came, we had less staff," says Perspectives CEO David Ruppell. "Richard would come to me and say, 'I feel like I'd like to get out in the community a little bit more. What can you do about the staffing?' And I didn't have a good answer for him because we had gotten rid of extra hours. We had to maintain safety at the house."

Gone, too, was another hope.

"I don't have much money," Rendine says. "I need a job. I don't have one."

"He would need a lot of support" in the workplace, says Ruppell. "And those supports aren't really there."

"We need more staff at my house," Rendine says. "We have six clients. Before, we had a big room.

Now they cut my room in half. I used to have a big room, now they made it half and half."

His reaction to the millions in statewide budget reductions that have led him here?

"It's just the state throwing these cuts. I don't know why. It's about money, I guess. Money, yup."

— gwmiller@providencejournal.com

(4010 277-7380

On Twitter: @GWayneMiller