R.I. praised for its care of mentally d

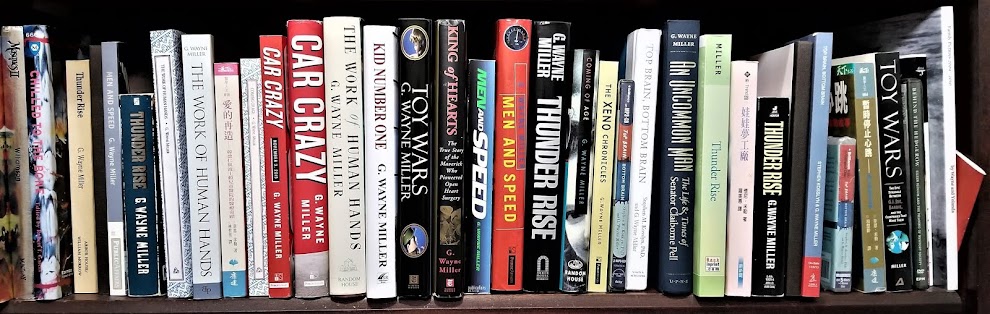

G. WAYNE MILLER

Publication Date: November 28, 1984 Page: A-01 Section: NEWS Edition: ALL

Part four of six parts.

[NOTE: The "Building New Lives" series examined both the mental health system and the system for care of the developmentally disabled, people who in 1984 were labeled "retarded" -- and many of whom lived in the now-closed Dr. Joseph H. Ladd Center in Exeter.]

|

| This is how the mentally ill were treated in RI 50 years ago. Courtesy: Providence Journal. For more on the institutional era, click here. |

For eight years, since his discharge from a public psychiatric hospital, William J. Moody has lived on these streets. For eight years, he has carried his earthly possessions in a valise, a shopping bag and a tattered gym bag. For eight years, he has been unable to find a job, or an apartment he can afford.

"A Bohemian," he fancies himself. "You know, more or less in a clean, bummy fashion."

When he has the money, Moody eats sardines and mayonnaise, or treats himself to Chinese food or a bowl of noodle soup. When he doesn't, he picks through dumpsters. At night, when the weather is fair, he sleeps in parks. When it isn't, he rides the subway until dawn or finds a steam grate or a warm tunnel.

Moody shuffles along East Third Street, a once respectable neighborhood gone to seed. Most of the buildings are boarded, run down, covered with unintelligible graffiti, revolutionary slogans, posters for new-wave bands named "Live Skull," "Brooklyn Dead" and "Alien Love."

Around the corner, men congregate near the Palace Hotel, a tumble-down flophouse. The men are young, middle-aged, old. Some snooze. Others drink, play cards, swap stories in gravelly voices. Their faces are tired and dirty. Their clothes are grimy. There is no dignity on these streets, only survival.

Moody gives his age as "60s." He is a tall, slim, toothless man with a crazy, crackling laugh and a fondness for clean clothes and porkpie hats.

Moody also is a schizophrenic. During his years on the streets, he has been spit on, beaten, stabbed, robbed, arrested. He has been thrown out of rooming houses, kicked off buses, denied medical care.

He is a victim - a victim of deinstitutionalization. In contrast to Rhode Island, where the movement has succeeded, New York is a national disgrace.

Like thousands of New York City's estimated 40,000 street people, Moody, a onetime drummer in a big band, spent years in an institution. Like the others, he was discharged without an apartment or a job, without psychiatric care, without much concern for what would happen to him.

"These people aren't getting shelter, food or clothing. Some are dying," says Dr. Frank R. Lipton, assistant professor of clinical psychiatry at New York University Medical Center. "For this group of people, we aren't even at square one. For these people, it's a mess."

NATIONALLY, deinstitutionalization has a mixed record. One of the most successful states has been Rhode Island, a national leader in the movement.

Other states, Wisconsin, Nebraska and Vermont among them, also have spent the time and money to care for people who have left institutions. A few, including Oklahoma and Arkansas, have rejected the movement and continue to operate large, overcrowded, unsafe institutions.

Still others, such as New York and California, rushed to empty institutions without putting in place all of the programs longtime patients must have to live decently in the community. In New York, 60,000 patients of state psychiatric hospitals have been released since 1965; estimates of those who need community help, but don't get it, run to 25 percent or more.

One result was predictable: a mounting cry to turn back the clock a half-century to when severely disabled people were routinely packed off to asylums.

"Attempts since the 1960s to 'deinstitutionalize' these patients and treat them in the community have succeeded only partially, and the failures are increasingly visible on the grates and gutters of urban America," the Wall Street Journal reported in August.

A Massachusetts Senate committee, in a report released two months ago, faulted that state's mental health department for being too zealous in its deinstitutionalization. The committee urged officials to consider reopening mental hospitals.

"The committee's investigation has uncovered sound evidence that hundreds upon hundreds of former patients are winding up in jail cells, emergency rooms, emergency shelters and walking the streets . . ." the report stated.

"One need only to walk the streets of Boston, Worcester or Springfield, or any other urban center, to see real-life examples of deinstitutionalization gone sour."

And in California, a nine-month state commission study concluded this year that group homes in the state were plagued by "abusive, unhealthful, unsafe and uncaring conditions . . . some residents are actually killed in facilities each year."

RHODE ISLAND places near the top among states that have done the job of deinstitutionalization well.

Yes, there are gaps in service, and there are some homeless mentally disabled people, but experts agree Rhode Island has spent the time and money to ensure that most people who leave the Institute of Mental Health and the Dr. Joseph H. Ladd Center will be able to live at something better than survival level.

Experts in mental health and retardation with national perspectives speak highly of how well Rhode Island has managed deinstitutionalization, and many have come here for firsthand looks. Not coincidentally, the first legislation encouraging national deinstitutionalization was introduced by a Rhode Island senator, John H. Chafee.

"You can see in a comparison of similar states with similar size how one can do a better job," says Neal B. Brown, director of the National Institute of Mental Health's community support program. "Rhode Island is doing a better job. A tremendous amount has been done in the last few years."

Harry C. Schnibbe, executive director of the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors, agrees. "It's working a hell of a lot better than in other places, I can say that," he remarks. "People are being taken care of when they get out of the facilities."

"There are only about three places in the country where there has been dramatic and consistent and persistent community development," says Thomas Nerney, a consultant to the U.S. Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services. "Rhode Island is one of them."

One recent survey by the National Institute of Mental Health, for example, shows that Rhode Island annually spends $61.56 per capita for private and public mental health services. Only three states spent more.

Another survey, by the University of Illinois at Chicago, showed that Rhode Island spent about $26 per capita for community services for the retarded. Only two of the 50 states spent more.

"Before you left the hospital, did anyone give you advice on how you were going to get by?"

Moody: "I was inquirin' while I was there but I couldn't make heads or tails out of what the people were sayin'."

"Do you have an income?"

"Yeah, I'm gettin' Social Security and an Army pension. About $450 per month. Four hundred fifty in 30 days. That's not much money in this city."

"Would you like to work?"

"Sure. Yeah. But you can't get anything these days. Everything seems to be filled. Then, on top of that, like I say, I don't have any identification. I can't tell them I belong to the union."

"What about an apartment?"

"Well, now, if I could afford it, and it more or less fitted my particular curricula, yeah, I'd go for it. I found a couple of places like that, but they're particular. You just can't get in there."

"What if someone found you a place. A state or city agency, say?"

"I'd love it. I'd go stark ravin' insane over it. Knowin' that I'd have my own private apartment? Would I like it? I'd end up paintin' the whole place in nothin' flat] Sure] I'd be crazy about that]"

RHODE ISLAND'S secret has been a combination of money, leadership, and a consensus that moving people out of institutions is cost-effective and humane. In few states has there been such agreement among legislators, the public and experts in the field.

These are among the ingredients of Rhode Island's success:

* Time.

Unlike other states, which rushed to empty institutions in the 1960s, Rhode Island didn't get into high gear until a decade later. That comparatively late start gave the state the chance to learn from others' mistakes.

Says Leona Bachrach, professor of psychiatry at the University of Maryland School of Medicine: "I think it's probably okay to suggest that you overcame some of the errors of some of the other states that proceeded very rapidly."

The majority of people leaving institutions were adequately prepared for new lives outside; people who had trouble outside were returned to the institutions until they were ready to try again. That was crucial. Large numbers of obviously disturbed people acting strangely or offensively would have created great public pressures to slow, or reverse, the movement.

* Size.

Rhode Island is a small state with only one public psychiatric hospital and a single public institution for the retarded - a built-in advantage to the architects of the movement. Many of the problems of larger states, including New York, have been related to the sheer magnitude of the task.

"New York inherited a terrible problem of numbers," says Joseph J. Bevilacqua, former director of the Rhode Island Department of Mental Health, Retardation and Hospitals. "New York had literally 40, 50 institutions. The calculus to move that number into community services is horrendously complicated. It's a gargantuan problem."

* Administrative leadership.

Both Bevilacqua and his successor, MHRH director Thomas D. Romeo, have made deinstitutionalization a top priority, fighting to channel money and resources away from Ladd and the IMH into community programs. They also brought on board, or promoted, division-level bureaucrats who shared their vision.

* Dedicated professionals.

Without competent front-line staff, quality services cannot be consistently provided. Although a few public and private workers have little interest in the people they serve, Rhode Island has been able to attract primarily qualified, dedicated professionals willing to work long hours at low pay in what is acknowledged to be a high "burnout" field.

* Community advocates.

One of the driving forces behind the movement has been the Rhode Island Association for Retarded Citizens. Less powerful, but still important, have been the Mental Health Association of Rhode Island and the Rhode Island Council of Community Mental Health Centers.

* Public support.

Although many group homes were met with stiff opposition in neighborhoods around the state, Rhode Island voters have never turned down a bond issue for development of community programs. Since 1967, 10 bonds totalling $90 million (including money for the IMH and Ladd) have been approved. The latest was an $8-million bond passed on Nov. 6.

Says Schnibbe: "That is one distinction that Rhode Island has that is substantially different from the rest of the country. Everybody wishes they could use it."

* Political leadership.

Many states have been frustrated by legislative squabbles over cost and purpose. For the last decade, the General Assembly and the governor have been committed to the program. In particular, Governor Garrahy and former Senate Majority Leader Rocco A. Quattrocchi have been key figures in mustering support.

* Federal money.

Unlike some states, Rhode Island has been unusually successful in attracting federal dollars. Even under the Reagan administration, the state has managed to get millions annually for community programs.

* Monitoring and control.

Although local providers administer many programs, allowing for flexibility and innovation state bureaucracies often lack, Rhode Island has kept control of overall programs through their financing. In those few instances where community workers have been found negligent, the state has moved quickly to discipline them or bring court charges.

* Legal action.

A 1977 federal suit by RIARC against the state accelerated the movement of people from Ladd and led to improvements at the institution.

* Media attention.

Investigations in the 1970s by the Rhode Island media, notably the Journal-Bulletin, focused attention on deplorable conditions at the IMH and Ladd. That attention made it impossible for legislators and MHRH administrators to ignore the problems of the state's mentally disabled, in or out of institutions.